Introduction

The twenty-first century has been characterized by an unprecedented pace of technological innovation, reshaping global economies and societies. In the context of India’s rapid digitization, which saw its digital economy grow 2.4 times faster than the national economy between 2014 and 2019, the issues of Digital/Cyber safety and financial literacy of the new entrants to the modern economy are not getting proper attention.

India’s aspiration to become a $5 trillion economy is increasingly reliant on a seamless digital infrastructure.However, this swift transition has introduced new and complex vulnerabilities. The present study addresses one such vulnerability: the proliferation of cyber fraud, specifically phishing, in geographically and demographically distinct districts within India. The analysis proceeds from a foundational observation that these emerging, technology-driven problems are not isolated phenomena but are intrinsically linked to pre-existing socio-economic and developmental challenges.This introduction chapter outlines the context from which the problem was identified, formalizes its scope, and details a proposed intervention designed to mitigate these threats by addressing their root causes at a community level.

Background of the Study

This study’s background is rooted in observations from two distinct districts: Ranchi in Jharkhand and Rajnandgaon in Chhattisgarh.While socio-demographically different—Ranchi is marked by a significant tribal population and chronic developmental issues like low literacy and poverty (listed in the Aspirational district category by NITI Aayog), while Rajnandgaon has a higher literacy rate (earlier, it was also an aspirational district, but not now)- both districts face similar agrarian challenges and a common underlying problem.The profound impact of poverty and a lack of livelihood opportunities leads to a cycle where low-skilled, poorly educated youth become susceptible to financial and cyber fraud, both as victims and as perpetrators.This framing positions cyber fraud not as an isolated technological issue, but as a modern symptom of pre-existing developmental challenges, highlighting the interconnectedness of social, economic, and technological factors.

Statement of the Problem

In the contemporary context, the challenge of cyber fraud and phishing has emerged as a critical threat to the integrity of the modern economy. This problem has assumed particular gravity in districts such as Ranchi, which has been referred to in media reports as the “New Jamtara,” a notorious hub for cybercrime. Empirical evidence illustrates the magnitude of this issue; for instance, 959 bank accounts were frozen in Ranchi within a single month on account of suspected phishing activities. Such developments highlight that the problem is neither isolated nor incidental, but systemic in nature.

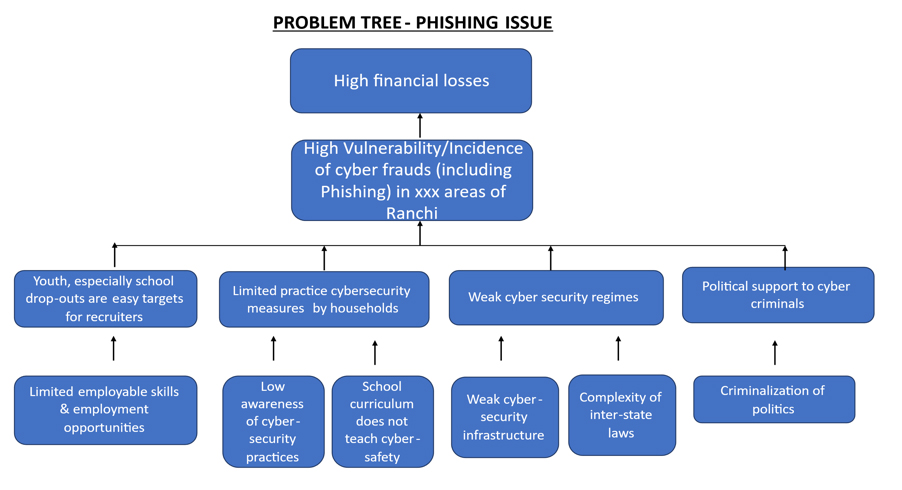

A systematic analysis of the issue, represented through a problem tree framework in Figure 1, demonstrates that cyber fraud in Ranchi stems from multiple, interlinked domains. The root causes are not singular but instead emerge from a confluence of social, economic, political, and administrative weaknesses. Among these, economic desperation resulting in unemployment often drives individuals toward illegal activities. Socially, there exists a mindset in certain sections of society that normalizes or tacitly condones such acts. Politically, inadequate attention to the issue perpetuates its existence, while administratively, weak cybersecurity infrastructure fails to prevent its proliferation.

To identify the most effective point of intervention, the classical economic principle of demand and supply has been employed as an analogical framework. In this approach, cyber fraud is conceptualized as a “product.” On the supply side are the perpetrators, which include organized rackets, lone actors, and international mafias. On the demand side are the victims, comprising teenagers, elderly individuals, non-working women, and small businesses. While the scattered, globalized, and often anonymous nature of supply makes it difficult to curtail directly, the demand side provides a more viable point of intervention.

The analysis thus reveals that the central root of the problem lies in the vulnerability of the victims. This vulnerability stems from a lack of adequate education and skills necessary to navigate the risks of a digitized world. Consequently, the framing of the issue suggests that solutions must extend beyond punitive law-and-order responses and instead focus on preventative strategies. Specifically, strengthening the human component of digital security through education-based interventions emerges as the most sustainable and impactful approach to addressing cyber fraud and phishing in the contemporary era.

Objectives of the Intervention

Based on the identification of “victim vulnerability” as the root cause, the present study proposes a structured intervention aimed at building digital resilience among the most susceptible populations.The primary objective is to equip high school and higher secondary students in the Rajnandgaon district with the necessary skills and understanding to navigate the digital economic world safely and confidently.

This overarching goal is supported by several strategic objectives:

- To develop and deliver a holistic, engaging awareness program on cyber safety and financial literacy through a series of quarterly workshops.

- To leverage the existing institutional structure of the school education system to ensure systematic and sustained delivery of the program.

- To create a cadre of local, community-based “Nudge-agents” or “ambassadors” from the student population who will disseminate cyber safety knowledge to their families and communities.

- To design the intervention with a low-cost, community-driven approach to ensure its financial, institutional, and social sustainability.

- To establish a replicable and effective roadmap for implementing large-scale awareness programs that can be emulated for other social development agendas.

The design of this intervention is built on the premise that students, as new entrants to the modern economy and frequent users of digital technologies, are ideally positioned to act as a catalyst for cognitive and behavioural change at the household level and, by extension, within society at large.

Delimitations of the Study

The present study is confined to a specific geographical, population, and programmatic scope to ensure a focused and measurable impact.

- Geographical Delimitation: The intervention is designed for and implemented within the Rajnandgaon district of Chhattisgarh (the district of current posting).

- Population Delimitation: The primary beneficiaries of the intervention are students of grades 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th, as this demographic is at the crucial juncture of formal education and entry into the workforce.

- Programmatic Delimitation: The study is focused on the specific issue of cyber fraud, with a particular emphasis on phishing.The intervention is delimited to the delivery of awareness and skill-building modules through a volunteer-based, workshop-driven model that utilizes pre-existing content from the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C) portal and other relevant sources.

The delimitations reflect the study’s adaptive design, which pivoted from a resource-intensive, agency-led model to a sustainable, low-cost, and community-driven approach due to real-world funding constraints.

Significance of the Intervention

The significance of this study extends beyond its direct impact on cyber safety.While the immediate goal is to reduce financial losses and the incidence of cyber fraud by lowering community vulnerability, it also holds the potential to propose a scalable, sustainable, and replicable model for large-scale social programs in resource-scarce environments.The intervention’s design was informed by a comparative analysis of past projects, emulating the successes of community-driven models like the ‘Pottha Laika’ project (Pottha laika in Chhattisgarhi language means ‘healthy child’, the project is a community-driven initiative to target malnutrition in children aged 0-5 years) of Rajnandgaon, while avoiding the failures of funds-intensive, agency-led initiatives like the BALA project (earlier in Ranchi). By leveraging community-driven solutions and minimizing costs, the project has established a new template for program implementation that has already been recognized by the district administration as a potential model for other social development agendas.

Research Questions

Based on the problem statement and the proposed intervention, the following research questions have been framed to guide the study:

- What is the quantitative impact of this intervention on the levels of cyber safety awareness among the target student population?

- To what extent can school students, when trained as awareness ambassadors, effectively disseminate cyber safety knowledge and influence behaviour at the household level?

- Is a volunteer-driven, low-cost intervention a more financially and socially sustainable model for large-scale awareness programs in a resource-constrained environment compared to a high-cost, agency-led model?

- How can the implementation roadmap developed for this intervention serve as a viable and effective template for designing and executing other social development programs in the district?

Hypotheses

Based on the review of related literature and the practical experience gained during the intervention’s design and implementation, the following hypotheses are proposed:

- It is hypothesized that a volunteer-driven, low-cost intervention will prove to be a more financially and socially sustainable model for large-scale awareness programs than a high-cost, agency-led model.

- It is hypothesized that students, when trained as “ambassadors,” will effectively disseminate cyber safety knowledge to their households, leading to a measurable increase in cyber safety awareness at the community level.

- It is hypothesized that there will be a significant, measurable increase in cyber safety knowledge and behavioral changes among the targeted student population as a result of the workshops.

- It is hypothesized that the implementation roadmap developed for this intervention will serve as a viable and effective template for designing and executing other social development programs in the district.

Limitations of the Study

The present study is subject to several limitations, most of which are external to the direct control of the researcher.

- Funding Constraints: The lack of a specific, dedicated budget created a significant bottleneck, necessitating a pivot from a planned agency-led model to a volunteer-driven one.

- Administrative Workload and Shifting Priorities of District Administration: The demanding nature of routine responsibilities and constantly shifting priorities often made it difficult to dedicate consistent, uninterrupted time to the intervention.

- Lack of Control over Volunteer Factors: The study does not have direct control over the individual effort, motivation, or availability of the Yuvodaya volunteers, as their commitment is subject to academic schedules.

These limitations, particularly the funding constraints, forced an innovative redesign of the intervention to a low-cost, community-driven approach, which has become a core strength of the project.

Definition and Explanation of Terms

The following terms are central to the study and are defined for clarity:

- Phishing: A form of cyber fraud in which an attacker, disguised as a trustworthy entity, attempts to deceive victims into providing sensitive information, such as personal details, passwords, or bank account numbers. Phishing is a subset of cyber fraud.

- Vulnerability: In this context, vulnerability is defined as the lack of adequate knowledge, skills, and awareness to safely interact with digital technologies and systems.The study identifies this as the root cause of cyber fraud.

- Yuvodaya Programme: A social service program coordinated by UNICEF that recruits a pool of youth volunteers, primarily college students, to engage in community assistance activities.

- Problem Tree: An analytical framework used to visually map the cause-and-effect relationships of a problem, identifying its root causes, immediate triggers, and broader consequences.

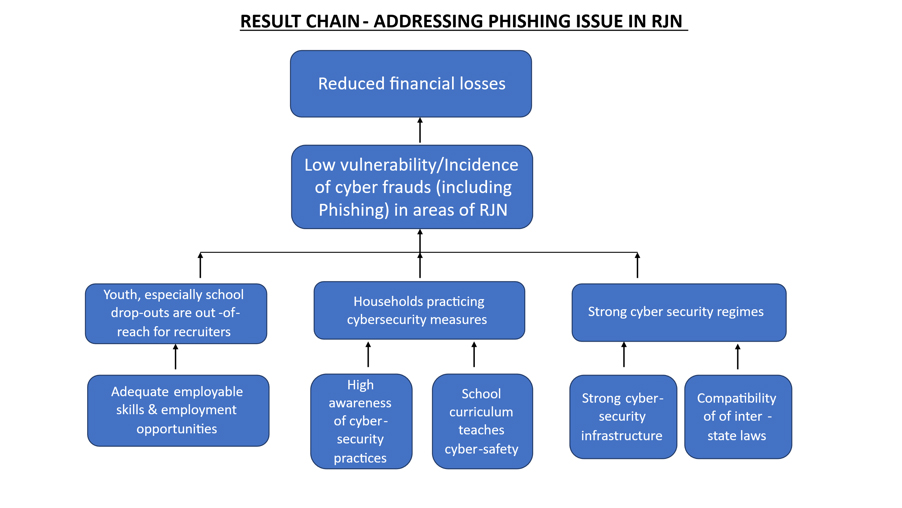

- Result Chain: A structured framework used to map an intervention’s planned inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and long-term goals.

District Overview

My experience in the PPiA Praxis Residency Programme has been defined by my immersion in two distinct yet socio-economically connected districts: Ranchi in Jharkhand and Rajnandgaon in Chhattisgarh. My work in each of these regions provided unique insights into the functioning of public, social, and economic institutions, as well as the intricate relationship between a district’s developmental context and the interventions designed to address its most pressing challenges. This chapter provides a detailed overview of both districts, highlighting their key characteristics, developmental statuses, and the way their unique contexts shaped the evolution of my cybersecurity and financial literacy intervention.

A Tale of Two Districts: Ranchi and Rajnandgaon

My journey began in the Ranchi district of Jharkhand, a region that is a part of the Chhota-Nagpur plateau. Its socio-demographic fabric is distinctly rural, with approximately 57% of the population residing in villages, and a significant tribal presence, comprising around 36% of the total population.The major tribal communities, such as the Santhal, Munda, and Oraon, are primarily agrarian but grapple with the challenges posed by the region’s sloppy and rocky topography. This challenging landscape makes irrigation difficult and leads to soil erosion, which negatively impacts agricultural productivity, a primary source of livelihood for these communities.

The developmental status of Ranchi, particularly among its tribal communities, is a reflection of these deep-rooted challenges. Literacy rates remain low, with male literacy at 47.9% and female literacy at 34.9% among Mundas, and an overall literacy rate of 56% among Oraons.Coupled with widespread poverty, a lack of quality education, poor nutrition, and limited livelihood opportunities, this has created a cycle of economic distress. These factors often compel male family members, and sometimes entire families, to migrate in search of daily wage labor.This context of economic desperation and a low standard of living has had a direct and alarming consequence: it creates a vulnerable pool of poorly skilled youth who, in their eagerness to find work, become susceptible to, and at times perpetrators of, financial and cyber frauds.It is within this complex environment that I began my work, noting media reports that have referred to Ranchi as a “New Jamtara”—a notorious hub for cybercrime, with 959 bank accounts frozen in a single month due to suspected phishing activities.

My work then transitioned to the Rajnandgaon district in Chhattisgarh. Unlike Ranchi, Rajnandgaon is geographically located in the central part of the state and has a relatively higher literacy rate of nearly 80%.The district represents a blend of tribal communities, including the Gond, Baiga, and Halba, and a significant agrarian population. Agriculture is the primary occupation, with a vast cultivated area. However, it shares a critical challenge with Ranchi: an over-reliance on a single crop, paddy, which has led to acute water scarcity and soil degradation.In response, the district has been actively promoting the cultivation of less water-intensive crops such as millets, maize, and pulses to ensure sustainable agriculture.

Key Institutions and Public Systems

The developmental landscape of both districts is supported by a network of public, social, and economic institutions. In Ranchi, foundational institutions like the Gram Panchayat and Gram Sabha play a crucial role in local governance and community needs assessment.Social institutions such as Women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs) are active in providing livelihood opportunities, offering health and nutrition counselling, and acting as a platform for interest aggregation before authorities.The district also leverages various governmental schemes and programs, such as the Johar Yojana and Birsa Harit Gram Yojana, to support farming and provide livelihood opportunities, as well as Abua-Awas Yojana and Tab-Lab facilities to address housing and education challenges.

In Rajnandgaon, the institutional ecosystem is dynamic and proactive. The district administration has fostered an environment of collaborative governance, which is reflected in a range of innovative, multi-sectoral projects:

- Health and Nutrition: The district has gained national recognition for its community-driven initiatives. The Pottha Laika program, a successful pilot to combat malnutrition, demonstrated a sustainable model by focusing on behavioral change and parental counselling using locally available food resources rather than expensive supplements.Similarly, the Swasth Noni initiative aims to tackle the alarmingly high prevalence of anaemia among adolescent girls through the convergence of health, education, and women and child development departments.The district also actively works on achieving saturation for schemes like the Ayushman Vay-Vandan Card for the elderly.

- Education: The district is committed to improving educational outcomes and has launched several ambitious projects. The Golden Triangle Programme and its component, Project Junior-G (another project designed by me), aim to prevent student dropouts by establishing a mentorship ecosystem where college students guide and support high school students.Career guidance seminars and the planned rollout of the Vinoba App for teacher empowerment further underscore the administration’s focus on building a robust educational system.

- Livelihood and Governance: The administration has championed projects to boost the local economy and strengthen governance. The SATHI Bazar Project, conceived as a “Swadeshi Mall,” provides a structured marketplace for farmers and SHGs, aiming to strengthen market linkages.The ‘Raj Bihan’ brand has been established to standardize and market products made by SHGs, giving a boost to the Mahila Lakhpati Didi scheme. On the governance front, initiatives like Good Governance Week, regular training for newly elected Sarpanchs, and community-led cleanliness drives (Swachhata Tyohar) are actively implemented to enhance public service delivery and citizen participation.

The Developmental Context and Its Relation to the Intervention

The profiles of Ranchi and Rajnandgaon reveal a critical insight: while their specific developmental challenges differ in scale and manifestation, both districts share a fundamental vulnerability born from the intersection of poverty, a lack of opportunities, and low levels of education.

In Ranchi, this vulnerability manifests as a direct link between socio-economic hardship and the proliferation of cybercrime. The absence of viable livelihood options pushes young people toward illicit activities, making the district a hotspot for cyber fraud.

In Rajnandgaon, despite a higher literacy rate and a more robust institutional framework, the underlying challenge of economic vulnerability persists, particularly for youth and women. The district’s proactive approach to governance and community engagement, however, provided an ideal environment for my intervention.The administration’s support for initiatives like the UNICEF-coordinated Yuvodaya program, which mobilizes college students for social service, was a crucial enabling factor.My intervention, which required a tech-savvy and community-oriented workforce to serve as “ambassadors” for change, found a perfect fit within the existing institutional landscape of Rajnandgaon. The district’s culture of social activism and its history of successful community-led projects, like Mission Jal-Raksha (a water conservation project led by Panchayats), confirmed that a grassroots, volunteer-driven model was not only feasible but also the most sustainable approach to tackling the problem of cyber fraud.

The developmental contexts of both districts, therefore, directly influenced the strategic evolution of my intervention. The challenges in Ranchi provided the impetus and problem statement, while the enabling environment and progressive institutional mechanisms in Rajnandgaon provided the perfect crucible for testing and implementing a sustainable, community-driven solution. This comparative experience underscored the central role of an adaptive approach, where an intervention’s success is contingent upon its ability to be flexible and align with the unique strengths and needs of the local context.

Intervention Design

Overview and Theory of Change

The intervention was designed to address the pressing and interconnected problem of cyber fraud, specifically phishing, which has proliferated in India’s rapidly digitizing economy.While the issue appears to be a technological one, a systematic analysis, using a problem tree framework and the classical law of demand and supply, revealed a deeper root cause: the vulnerability of the victims.This vulnerability stems from a critical lack of digital education and financial literacy, which is particularly acute among new entrants to the modern economy who are often inadequately equipped to navigate its complexities and risks.

My theory of change is predicated on a preventative, education-based approach aimed at “cutting the demand side or receiving side (victims)” for cyber fraud by strengthening the human component of digital security. Rather than focusing on a difficult-to-control supply side (perpetrators) of scattered, and often international, criminal rackets, the intervention directly targets the vulnerability of the most susceptible population: high school and higher secondary students. The central premise is that by empowering this demographic with cyber safety knowledge and skills, they will not only protect themselves but also serve as catalysts for broader societal change. The intervention positions these students as community-based “Nudge-agents” or “ambassadors,” who will disseminate their learnings to their families and social circles, thereby initiating a chain reaction of cognitive and behavioural change at the household level and, eventually, throughout the wider community. This strategy is built on the belief that a direct and trustworthy source of knowledge, planted within the household, is the most effective way to foster digital resilience from the ground up.

Programmatic Design and Beneficiaries

The intervention, titled the Cyber Literacy to School students program, was structured as a holistic, engaging, and multi-activity awareness module. The primary beneficiaries are students in grades 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th in the Rajnandgaon district of Chhattisgarh. This specific population was chosen because these students are at a critical juncture in their lives, either as they enter higher education or the active workforce. The program aims to make these individuals capable of safeguarding themselves and others from cyber fraud. By extension, their families and the wider community are the secondary beneficiaries, receiving indirect but meaningful exposure to cyber safety practices through the students.

The program’s design includes a series of quarterly workshops to ensure a systematic and sustained delivery of the content over the course of an academic year. Each workshop is planned as an advancement of the previous one, ensuring that students build their knowledge incrementally. To maintain engagement and active participation, each session is designed to incorporate a variety of elements, including audio-video presentations, informational materials, live demonstrations, and interactive games.

The intervention’s objectives are clearly defined and serve as a roadmap for the program’s intended outcomes:

- Develop and Deliver: To create and deliver a holistic awareness program on cyber safety and financial literacy through quarterly workshops.

- Leverage Institutional Structures: To utilize the existing school education system for sustained delivery of the program.

- Create Community Ambassadors: To establish a cadre of “Nudge-agents” from the student population who will disseminate cyber safety knowledge to their communities.

- Ensure Sustainability: To design a low-cost, community-driven approach that is financially, institutionally, and socially sustainable.

- Provide a Replicable Roadmap: To establish a replicable and effective model for implementing large-scale awareness programs for other social development agendas.

Implementation Architecture: A Pivot to Sustainability

The project’s implementation architecture evolved significantly from its initial conception to its current form, largely as a result of a lack of dedicated funding. The original plan, informed by an externally funded initiative in Ranchi, involved onboarding a specialized implementing agency with professional domain experts. When this proved unfeasible, the intervention underwent a fundamental redesign guided by the principles of adaptive leadership and the valuable lessons learned from successful community-driven initiatives in the district, such as the ‘Fasal Sangosthi’ (mass counselling sessions to nudge farmers to move away from paddy and adopt crop diversification).

The revised implementation plan hinges on three key strategic pivots:

- Volunteer-Driven Workforce: The first and most significant pivot was the decision to replace the professional agency with a volunteer workforce.After being appointed as the district Nodal Officer for the Yuvodaya program—a UNICEF-coordinated initiative that recruits college students for social service—I found a ready pool of educated, tech-savvy, and service-oriented youth.To date, more than 1,000 such volunteers have been recruited and strategically mapped to the district’s four administrative blocks and specific schools, ensuring a consistent and localized approach.

- Curation Over Creation: The second pivot addressed the content development challenge. Instead of relying on a firm to create new training materials—which was no longer an option due to funding constraints—I shifted to curating existing, credible resources. I collaborated with the District Cyber Cell to identify and organize a comprehensive pool of training and IEC (Information, Education, and Communication) materials from authoritative sources, including the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C) portal under the Union Home Ministry. This approach ensures that the program content is both cost-effective and reliable.

- Community-Based Training: The third pivot involved the training of the volunteers themselves. To transform the Yuvodaya volunteers into effective resource persons, a structured, five-day training and orientation program was conducted in July 2025. These sessions were held in batches to ensure quality interaction and were led by officials from the District Cyber Cell and the Police Department. Once trained, these volunteers were provided with a school visit schedule to carry out the awareness sessions. This model leverages local resources and expertise, making the entire process financially and socially sustainable.

The implementation follows a strategic timeline that was adapted to align with the academic calendar to avoid delays. After recruiting the volunteers and curating the content, the training sessions were held in July following college examinations. This was immediately followed by the first round of quarterly workshops in schools. A system of continuous monitoring and quarterly progress surveys has been established to allow for real-time course correction and ensure the program’s effectiveness.

Monitoring and Evaluation Framework

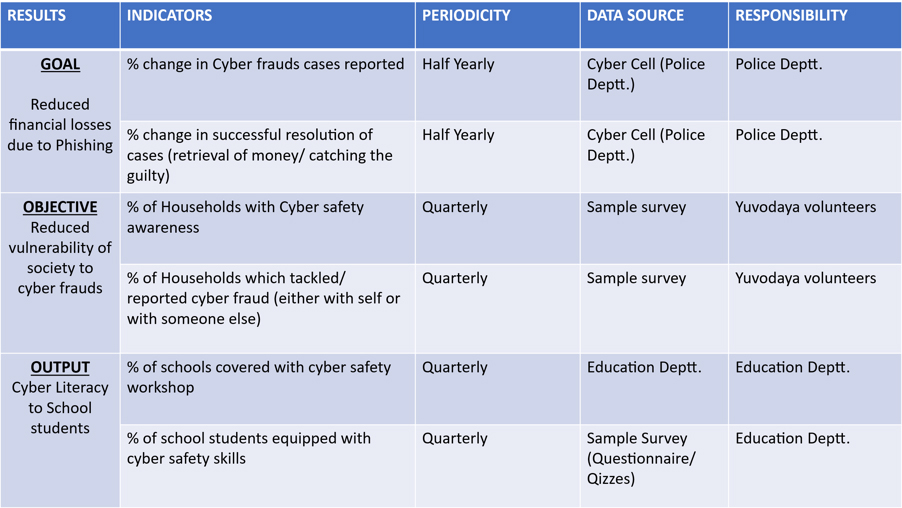

To ensure accountability and measure the impact of the intervention, a Result Chain framework (Figure 2) was developed to systematically track the project’s progress. This framework translates the intervention’s goals, objectives, and outputs into measurable indicators, each with a defined periodicity, data source, and responsibility for data collection, as shown in Table 1.

The framework’s primary goal is to achieve a reduction in financial losses due to phishing, which will be measured by the percentage change in reported cyber fraud cases and the successful resolution rate of those cases, with data sourced from the District Cyber Cell on a half-yearly basis.

The intervention’s main objective is to reduce society’s vulnerability to cyber fraud. This will be assessed quarterly through sample surveys conducted by the Yuvodaya volunteers to measure the percentage of households with cyber safety awareness and the percentage of households that have successfully tackled or reported a cyber fraud.

The immediate output of the intervention is to achieve cyber literacy for school students. This is measured quarterly by tracking the percentage of schools covered by the workshops and the percentage of students equipped with cyber safety skills, with data collected by the Education Department through sample surveys.

This structured approach, with its clear chain of results, provides a robust basis for monitoring and evaluation, demonstrating a commitment to a data-driven and evidence-based approach to social change.

Intervention Implementation

The transition of a conceptual framework into a tangible, on-the-ground intervention is often an exercise in adaptive leadership, where theoretical design meets the realities of resource constraints and administrative dynamics. This chapter details the unfolding of the cyber fraud intervention, from its initial stakeholder discussions to its current status as a functioning, community-driven program. It highlights the strategic pivots made in response to real-world challenges, articulates the key milestones achieved, and presents a clear picture of the project’s physical and financial progress.

The Unfolding of the Intervention: An Adaptive Journey

The journey of implementing this intervention began with a series of in-depth discussions with various stakeholders, including students, teachers, Panchayati Raj Institution (PRI) members, and district officials. These initial engagements served a dual purpose: to gain a deeper understanding of the issue’s ground realities and to garner support for the proposed solution. While these consultations were critical, they also presented a significant logistical challenge, as scheduling standalone meetings proved difficult due to the time constraints and demanding workloads of all involved parties.

In a pivotal moment of adaptive problem-solving, a new strategy was adopted: integrating cybersecurity discussions into existing, pre-scheduled forums. By using large-scale gatherings such as district-level grievance redressal camps, Kisan Melas, and departmental training programs as platforms, I was able to engage with a diverse and wider audience in a time-efficient manner. This approach not only garnered valuable feedback but also ensured that the core ideas of the project were widely disseminated and received positive support from the district authorities, confirming the relevance and feasibility of the initiative.

A major turning point in the intervention’s implementation architecture was the direct result of a significant financial bottleneck—the lack of dedicated funding. The initial plan, a professionally executed, agency-led model, had to be abandoned. This challenge, however, forced a fundamental pivot to a low-cost, community-driven model. This strategic shift was inspired by the successes of local initiatives such as the Pottha Laika project, which had effectively addressed malnutrition by leveraging community resources.

4.2 Implementation Timeline and Milestones

The execution of the intervention has followed a clear, periodic timeline, with key milestones achieved at each phase.

- Initial Stakeholder Engagement: Over the period leading up to the program’s formal launch, I conducted focused discussions with community and administrative stakeholders across both Ranchi and Rajnandgaon districts. These engagements, which were integrated into existing meetings and events, were critical for refining the intervention’s scope and gaining buy-in from key departments, including the District Cyber Cell and the Education Department.

- September 2024 – June 2025: Recruitment and Content Curation: Upon my appointment as the Yuvodaya program Nodal Officer in September 2024, the recruitment of youth volunteers from various colleges across the district began in earnest. Simultaneously, a comprehensive pool of training and IEC (Information, Education, and Communication) materials was curated with the support of the District Cyber Cell, drawing heavily from resources like the I4C portal.

- July 2025: Volunteer Training and Capacity Building: From July 7th to July 11th, a structured, five-day training and orientation program was conducted for the Yuvodaya volunteers. The sessions were organized in five batches of 200 volunteers each to ensure high-quality interaction. Officials from the District Cyber Cell and the Police Department served as trainers, equipping the volunteers with the necessary cyber safety knowledge and communication skills to act as effective resource persons.

- Post-July 2025: Program Launch in Schools: Following the training, the volunteers were provided with a school visit schedule, prepared in coordination with the education Department.They were strategically mapped to the district’s four administrative blocks and specific high schools to ensure consistent outreach. The program was formally launched in August 2025 with the first round of quarterly workshops for students in grades 9th to 12th.

This structured approach, with its defined milestones and strategic alignment with the academic calendar, has ensured that the intervention moves forward systematically, preventing delays and institutionalizing the program within the existing educational framework.

Physical and Financial Achievements

The intervention, despite a lack of dedicated funding, has achieved significant physical and financial milestones.

Physical Achievements:

- Volunteer Cadre: The most notable achievement is the successful recruitment and training of over 1,000 Yuvodaya youth volunteers, creating a sustainable cadre of cyber safety ambassadors. In the first phase of the programme implementation, these volunteers have been strategically mapped to the 50 high schools and higher secondary schools across the district, ensuring that the program has a wide and consistent reach.

- Program Integration: The intervention has been successfully embedded within the formal school education system, moving it beyond a one-time campaign to a sustained, year-long learning process. This institutionalization ensures that students are not only introduced to the concepts of cyber safety but are continuously engaged with them throughout the academic year.

- Educational Outreach: The program has successfully initiated the first round of its quarterly workshops in schools for the targeted student population. Early feedback from teachers, parents, and PRI members is encouraging, noting that students are actively discussing their learnings with their families, demonstrating the program’s effectiveness in fostering behavioural change at the household level.

Financial Achievements:

- The intervention’s most significant financial achievement is its ability to operate as a low-cost, community-driven model, effectively circumventing the hurdle of a lack of dedicated funding. By relying on a volunteer workforce and curating pre-existing content from sources like the I4C portal, the program has eliminated the need for a costly implementing agency and the financial burden of content creation.

- The project’s design was deliberately kept financially lean, which has made it a “ready-made template” for other departments to emulate for their own social development agendas, such as the recent ‘Swasth-Noni program’ (Healthy girl child) to address anaemia in adolescent girls. This demonstrates that a sustainable and impactful intervention does not require a large budget but rather a strategic approach to resource management and community engagement.

Broader Implications and Future Outlook

The implementation of this intervention reflects a broader shift in India’s developmental landscape, where community-led initiatives are increasingly seen as the most viable path to sustainable social change. Government schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Gramin Digital Saksharta Abhiyaan (PMGDISHA) have also recognized the importance of targeting digitally illiterate students in rural areas and empowering them to bridge the digital divide. This program aligns with the core principles of the Digital India mission, which aims to improve digital literacy and connectivity across the country.

My experience highlights that while government efforts, such as the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C), are crucial for providing a robust security framework and credible resources, the final mile of delivery and behavioural change is best accomplished by a ground-up, community-led approach. As CRY India’s (Child Rights and You) research has noted, sustainable change comes when communities themselves lead the way, with children acting as catalysts for change within their families.

This intervention, forged in a context of resource scarcity and administrative constraints, has emerged not only as a solution to cyber fraud but also as a powerful template for district-level governance. By leveraging existing institutional structures, prioritizing community participation, and maintaining a low-cost model, the program demonstrates how local strengths can be harnessed to achieve significant social change. The roadmap developed during this process provides a clear and replicable model for other departments, confirming that the most impactful interventions are often those that are rooted in the community and designed to be both financially prudent and socially sustainable.

Outcomes And Impact

The success of any intervention is ultimately measured not by its design, but by its tangible effects on the lives of people, the resilience of institutions, and the enduring change it fosters within public systems. This chapter reflects on the outcomes and impact of the cyber fraud intervention, offering a critical analysis of its effects on households, institutions, and the public system. It highlights the systemic shifts achieved, discusses the adaptive challenges navigated, and assesses the long-term sustainability and scalability of the model.

Outcomes and Impact on Communities, Households, and Individuals

The immediate and most visible impact of the intervention has been at the grassroots level, directly affecting the lives of students and their families. The program’s core theory of change—that students, as new entrants to the digital economy, could become “ambassadors” for change—is already bearing fruit.

A Spark for Behavioural Change: The feedback received from a range of stakeholders, including teachers, parents, and members of the Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs), has been overwhelmingly encouraging. It is evident that the workshops have not remained isolated academic exercises; students are actively discussing their learnings with their families and friends. This validates the foundational premise of the intervention, demonstrating its ability to initiate cognitive and behavioural change at the household level. This phenomenon, often referred to as a “ripple effect,” is a hallmark of successful community-led initiatives, where children act as catalysts for awareness and action within their immediate social circles. By providing a trustworthy, direct source of information, the program is empowering households to better identify and protect themselves against cyber threats, thereby reducing their fundamental vulnerability to fraud.

A Significant Change Story: The power of this approach became profoundly clear through a seemingly unrelated observation. While conducting stakeholder discussions and field visits for the cyber safety program, I became aware of the chronic issue of anaemia among adolescent girls in the district. This finding, brought to light through the very process of engaging with the community for this intervention, led to the conceptualization of a new district-wide program- ‘The Swasth Noni’ initiative to tackle the issue. This anecdote serves as a powerful testament to the intervention’s systemic impact; its methodology of using existing community forums to collect data and engage stakeholders has emerged as a valuable, cost-effective tool for addressing other pressing social issues, confirming its utility beyond its primary domain.

Impact on Institutions and Public Systems

The intervention’s influence extends far beyond the household, acting as a force for positive change within the public system itself. It has successfully negotiated several systemic and adaptive challenges to establish a new, more sustainable model for governance.

Navigating Adaptive Challenges: From an Adaptive Leadership perspective, the intervention’s journey has been a masterclass in distinguishing between technical problems and adaptive challenges. The initial plan to hire an implementing agency, while technically sound, was not a sustainable solution in a resource-constrained environment. The adaptive challenge lay not in finding a firm, but in reimagining how to deliver the program with existing, internal resources. My appointment as the district Nodal Officer for the Yuvodaya program was a critical adaptive pivot. Instead of viewing the lack of funding as a final roadblock, it was reframed as an opportunity to leverage a ready-made pool of o tech-savvy youth volunteers, thereby transforming a vulnerability into the intervention’s core strength.

This process directly reflects the lessons from past projects in the district. The failure of the externally funded BALA project, which was cancelled due to a lack of funds and shifting priorities, stood in stark contrast to the success of the community-driven Pottha Laika project, which effectively addressed malnutrition through a low-cost, participatory model.The cyber safety intervention deliberately emulated the successes of Pottha Laika, demonstrating an ability to negotiate systemic limitations by building upon local strengths rather than external dependencies.

Systemic and Policy Impact: By embedding the program within the formal school education system, the intervention has moved from a temporary campaign to a sustained, institutionalized process. This is a critical systemic achievement, ensuring that the learning is continuous and not dependent on periodic funding cycles. The use of analytical tools like the

Problem Tree and Result Chain frameworks resonated deeply with government officials, providing a clear and logical structure that helped to elevate cybersecurity as a key focus area within the broader digital agenda.

The intervention’s roadmap, forged through a process of creative problem-solving and adaptation, has been recognized by the district administration as a potential “ready-made template” for other departments to emulate. This is perhaps the most significant systemic outcome, as it demonstrates a new, more effective way of delivering large-scale social programs in resource-scarce environments. It aligns with and reinforces broader national efforts like the Pradhan Mantri Gramin Digital Saksharta Abhiyaan (PMGDISHA), which also prioritizes empowering digitally illiterate students in rural areas, and the Digital India mission. The program’s initial success provides tangible evidence that a ground-up, community-led approach, is a powerful model for bringing sustainable behavioural changes.

Scalability and Long-Term Sustainability

The core design principles of the intervention ensure its long-term viability and potential for scale.

- Financial Sustainability: The program’s low-cost, community-driven model is its greatest asset. By relying on a volunteer workforce and curating pre-existing content from authoritative sources like the I4C portal, it has eliminated the need for a costly implementing agency and the financial burden of content creation. This design makes it significantly less vulnerable to the budget cuts and shifting priorities that plagued other initiatives.

- Institutional Sustainability: By institutionalizing the program within the Education Department, the intervention is now embedded in an existing system, ensuring its continuity. The roles and responsibilities of the Yuvodaya volunteers and the Education Department have been clearly defined, creating a robust framework for sustained delivery.

- Social Sustainability: The program is built on the active participation of the community itself. By training youth from the district as “ambassadors,” it fosters a sense of local ownership and shared responsibility. This is a crucial element for long-term social change, as sustainable change happens when communities lead the way. The encouraging feedback and active engagement of students and parents are early indicators of a collective movement, demonstrating a shift from passive receptivity to active participation.

Evidence and Indicators: While the long-term goal of reducing financial losses due to cyber fraud will be measured over time by the District Cyber Cell, the Result Chain framework provides clear, immediate indicators of success. The initial workshops have already confirmed the achievement of key outputs, such as “schools covered” and a clear increase in awareness among students, as evidenced by their willingness to discuss the topics with their families.The Yuvodaya program has created a trained cadre of over 1,000 volunteers, a substantial physical achievement that provides a clear pathway for scaling the program to every high school and higher secondary school in the district. A survey conducted in September, i.e, after a month of the first conduction of quarterly workshop in the schools, showed that more than 82% students, who participated in the workshops, discussed the cyber awareness issue with their family and friends. The programme is under implementation, and the initial results are quite promising.

In conclusion, the intervention’s outcomes and impact are a compelling narrative of adaptation and resilience. It has not only addressed a critical modern-day problem but has done so by creating a template for a new kind of governance—one that is lean, agile, community-led, and, most importantly, sustainable. The intervention’s true legacy may not be in the number of frauds prevented, but in its successful demonstration that local communities, when properly leveraged and empowered, can become the most potent force for enduring social change.

Reflections And Learnings

The journey of conceptualizing, designing, and implementing this intervention has been a profound learning experience, offering insights that transcend the specific problem of cyber fraud. It has been a process of navigating complex public systems, leveraging community strengths, and adapting a theoretical model to the realities of a resource-constrained environment. This chapter articulates the key learnings derived from this experience, categorized into four distinct typologies.

Public Institution Learning

Working within the public system provided a clear and pragmatic understanding of its operational dynamics. I learned that the traditional top-down approach to project implementation, while procedurally sound, is often brittle and susceptible to external shocks. The original plan to onboard a specialized implementing agency, a technically straightforward solution, was ultimately rendered unviable by the inherent financial constraints and shifting administrative priorities of the district. This experience, taught a critical lesson: an intervention’s strength lies not in the perfection of its design, but in its ability to adapt to the system’s underlying conditions.

I learned to negotiate the system’s limitations by adopting a more agile approach. Instead of creating new, standalone mechanisms, I strategically embedded the intervention within existing government platforms. For instance, rather than organizing difficult-to-schedule, dedicated meetings, I leveraged pre-scheduled forums such as district-level grievance redressal camps and departmental training programs to gather stakeholder feedback and garner buy-in. This proved to be a powerful and time-efficient way to secure support from key departments like the District Cyber Cell and the Education Department. Furthermore, I recognized the importance of framing the intervention in a way that aligns with the broader priorities of the district administration, lending it legitimacy and ensuring inter-departmental cooperation. My experience confirms that for an idea to take root in a complex public system, it must speak the language of governance—it must be low-cost, replicable, and contribute to the system’s mandated goals.

Community Institutions Learning

The most transformative learning from this intervention relates to the power and potential of community institutions. The initial plan was to rely on a professional agency, but a lack of funding forced a critical pivot to a community-driven model. This strategic shift, inspired by the successes of the Pottha Laika project in combating malnutrition, the Fasal-Sangosthi initiative to nudge towards crop diversification, demonstrated that when properly leveraged, local community resources and institutions can be the most potent force for sustainable social change.

The Yuvodaya program, provided a ready and enthusiastic pool of college student volunteers. This pre-existing community institution, with its cadre of educated, tech-savvy youth, became the backbone of the intervention. Instead of viewing the community as passive beneficiaries, the project redefined them as active partners and “ambassadors” of change. By training these volunteers to become master trainers, the intervention did more than just disseminate information; it built a lasting local capacity for knowledge dissemination and awareness building. This process fostered a sense of local ownership and shared responsibility, which is the cornerstone of any sustainable social initiative. As organizations like CRY have also noted, sustainable change comes when communities themselves lead the way. The learning here is clear: an intervention for the community must be led by the community itself, leveraging its existing strengths and institutions to foster long-term resilience from the ground up.

Impact Learning: Scale and Sustainability

The intervention’s design, born out of necessity, has become a powerful model for achieving scale and sustainability in resource-constrained environments.

- Financial Sustainability: The program’s core strength is its low-cost model, which has made it resilient to the funding constraints that plague many projects. By relying on a volunteer workforce rather than a paid agency and by curating content from authoritative, free-to-use sources like the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C) portal, the intervention has demonstrated that a lack of budget does not have to be a roadblock to impact. This approach is a testament to the idea that a strategically designed, lean program can be more sustainable than a high-cost, resource-intensive one.

- Institutional Sustainability: The intervention’s seamless integration into the formal school education system is a critical institutional achievement. By embedding cyber safety into the curriculum for students in grades 9th to 12th, the program has become a sustained learning process rather than a one-time campaign. The clear delineation of roles between the Yuvodaya volunteers and the Education Department ensures that the program has a robust, long-term institutional framework, ensuring its continuity well beyond the initial implementation phase.

- Social Scalability: The Yuvodaya program has created a trained cadre of youth volunteers, a substantial physical achievement that provides a clear pathway for scaling the program to every high school and higher secondary school in the district. This model, which trains local youth to act as “ambassadors” to their families and communities, is infinitely scalable, as it taps into a self-renewing, localized workforce. The positive feedback and behavioural changes observed in the initial phase serve as evidence that this model has the potential to reach and influence every household in the district. This approach aligns with broader community-led digital literacy efforts across India.

Policy Learning

The intervention has provided critical insights into policy work, particularly through the lens of Adaptive Leadership. It has become a case study in how to navigate the complex interplay between technical problems and adaptive challenges, and how to create a new paradigm for governance.

Distinguishing Technical and Adaptive Challenges: The project’s most significant learning from a policy perspective was the clear distinction between the “technical” problem of delivering a cyber safety program and the “adaptive” challenge of doing so in a system marked by resource scarcity and administrative inertia. The solution was not to seek more funding (a technical approach that had already failed) but to fundamentally change the delivery model to one that was agile and community-driven. This adaptive approach, which reframed limitations as opportunities for innovation, is a key insight that can inform future policy design in India’s developmental landscape.

A New Template for Governance: The implementation roadmap, forged through a process of creative problem-solving and adaptation, has been recognized by the district administration as a potential “ready-made template” for other departments to emulate. This is the most powerful systemic outcome of the intervention. It demonstrates that a new, more effective way of delivering large-scale social programs is possible—one that is lean, agile, and community-led. This approach aligns perfectly with and reinforces broader national efforts like the Pradhan Mantri Gramin Digital Saksharta Abhiyaan (PMGDISHA), which also prioritizes empowering digitally illiterate students in rural areas, and the Digital India mission, which aims to improve digital literacy and connectivity across the country.

My experience confirms that while central government bodies like the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C) provide the foundational resources and a robust national framework, the final mile of delivery and behavioral change is most effectively accomplished through a ground-up, community-led model. This convergence of top-down policy and bottom-up execution is the key to bridging the digital divide and ensuring that the benefits of India’s rapid digitization reach every citizen, regardless of their location or socio-economic background. The intervention’s true legacy may not be in the number of frauds prevented, but in its successful demonstration that local communities, when properly leveraged and empowered, can become the most potent force for enduring social change.

References

Media Reports:

Similar Programmes:

Data And Statistics

District Cyber Cell, Rajnandgaon, Chhattisgarh