Executive Summary

This dissertation documents my journey as a Public Policy in Action (PPiA) Praxis Learner in Saraikela Kharsawan district, Jharkhand, and focuses on the design and implementation of the Agro Tech Park (ATP) intervention in Kuchai block. It synthesises my quarterly reflections, intervention documents, and field experiences into a structured narrative intended for both policy practitioners and academics.

Background and Context

Saraikela Kharsawan is a district of paradoxes. On one hand, it hosts the Adityapur Industrial Area, one of Asia’s largest auto-component hubs, employing thousands in over 1,600 industrial units. On the other hand, much of its rural population continues to rely on agriculture characterised by low productivity, poor mechanisation, and limited irrigation. Younger generations, attracted to factory jobs, increasingly disengage from farming, leaving it vulnerable to stagnation.

The fellowship began with a diagnostic process that identified this paradox as a central challenge: industry was expanding, but agriculture was being left behind. This imbalance threatened both livelihoods and long-term sustainability. The Agro Tech Park was conceived as a response — a way to make agriculture viable again by embedding innovation, training, and institutional ownership at the district level.

The Intervention: Agro Tech Park

The Agro Tech Park was designed as an integrated demonstration and training hub. Its core idea was that if farmers could see and practice modern methods, supported by institutions that provided ownership and market linkages, they would be more likely to adopt them. The park combined diversified components — horticulture, mushroom cultivation, livestock, fisheries, and honey production — into a circular farming model where waste from one activity could be reused in another.

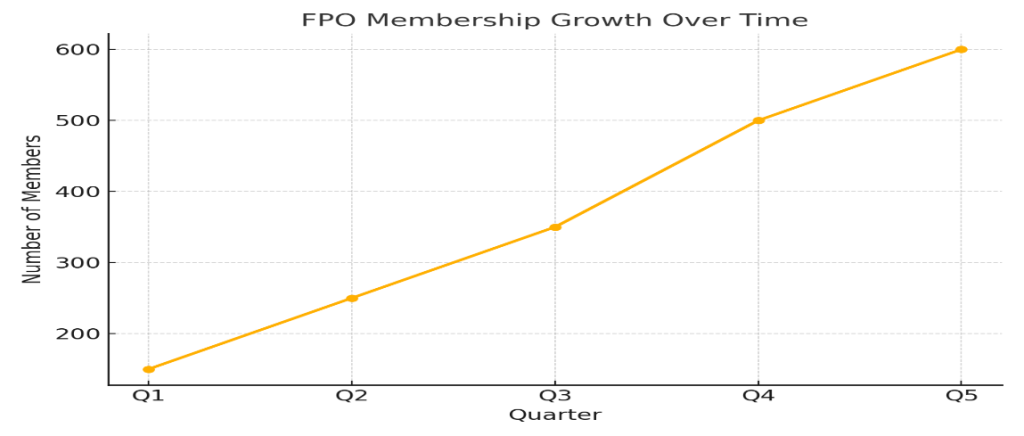

Institutionally, the Agro Tech Park was anchored by a Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO), which began with 150 members and aimed to expand to 750. The FPO was tasked with managing assets, marketing produce, and reinvesting profits. Oversight was provided by the District Livelihood Coordination Committee (DLCC), chaired by the Deputy Commissioner, which brought together departments such as Agriculture, Horticulture, Animal Husbandry, Fisheries, and JSLPS. This convergence-driven design was meant to ensure resilience and reduce dependence on individual champions.

Implementation

The Agro Tech Park moved steadily from design to practice. Land was secured in Kuchai block after negotiations with villagers, who initially resisted the loss of their grazing and river pathway. A compromise was reached by building an alternate path, demonstrating that community concerns could be addressed with sensitivity.

Infrastructure was developed, including livestock sheds, mushroom cultivation rooms, fish ponds, and storage units. Training programs began, with the first three-day session engaging 77 farmers. These were deliberately practical, with sessions conducted in plots and sheds rather than classrooms. Women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs) showed strong participation, especially in mushrooms and poultry, while youth showed interest in horticulture.

Funding volatility emerged midway as the Government of India withdrew Special Central Assistance (SCA) for LWE-affected districts, citing Saraikela Kharsawan’s changed status. This forced a pivot toward departmental convergence, corporate social responsibility (CSR) engagement, and early revenue generation by the FPO. By selling mushrooms, honey, and fish in weekly haats, the FPO began demonstrating financial viability.

The final phase (Quarter 6) brought both new opportunities and setbacks. A district-level convergence committee was constituted, providing stronger oversight and coordination across departments. Plans were also initiated to bring NGOs and private FPOs on board through Expressions of Interest (EOIs), aimed at strengthening technical and marketing capacities. At the same time, challenges like a goat mortality incident revealed gaps in veterinary support and underscored the fragility of livestock-based interventions. These experiences highlighted that infrastructure alone was insufficient; technical systems and institutional backstopping were equally vital.

Outcomes

At the household level, pilot cycles generated modest but meaningful income gains. Farmers reported growing confidence in agriculture as they saw mushrooms and fish being sold successfully. For women’s groups, the Agro Tech Park created new livelihood opportunities and linked them to Mission Lakhpati Didi.

At the institutional level, the FPO expanded its membership, managed initial marketing, and began assuming operational responsibility. The SHGs transitioned from savings-and-credit activities into income generation. The DLCC provided a platform for convergence, and the Q6 convergence committee further formalised institutional oversight.

At the systemic level, adaptive challenges came to the fore. Bureaucratic transfers and funding volatility threatened progress, yet persistent advocacy and visibility in district reviews helped sustain momentum. The unintended outcomes were also notable: high-mast lighting installed near the Agro Tech Park benefitted a nearby school and health centre, while Kuchai block itself gained renewed administrative visibility, shifting its image from an LWE-affected zone to a site of innovation.

Learnings

The Agro Tech Park produced insights across four dimensions. Public institution learning showed that bureaucratic continuity is fragile and convergence requires orchestration. Community institution learning highlighted both the risks of elite capture in FPOs and the transformative potential of SHGs when given practical entry points. Impact learning revealed that small wins matter, sustainability is dynamic, and scalability depends on embedding models into systems. Policy learning pointed to the risks of funding volatility, the value of adaptive leadership, and the importance of persistence in keeping projects on the administrative agenda.

Two cross-cutting lessons stood out from the final phase: trust must be continuously nurtured even through setbacks, and persistence — the everyday nudging of officials and institutions — is as important as design or strategy in sustaining innovation.

Conclusion

The Agro Tech Park remains at an early stage, but it has begun to reshape perceptions around agriculture in Kuchai block. It demonstrated that farming can be viable when linked to modern practices, collective ownership, and institutional convergence. For practitioners, it offers a replicable model that integrates training with sustainability. For policymakers, it underscores the need to buffer local innovations against volatility and anchor them in institutions rather than individuals. For me, it was a transformative journey that reaffirmed the belief that development is about people first, policies second.

Introduction

The Praxis Public Policy in Action (PPiA) Fellowship gave me the chance to step into the world of district administration, not just as an observer but as someone working within the system. Unlike the classroom, where we mostly read and discuss theories, this fellowship placed me in the field and asked me to respond to real challenges faced by people and institutions. My time in Saraikela Kharsawan district, Jharkhand, became the setting for this journey.

This dissertation is a record of that experience. It is built on the reflection papers I wrote across five quarters and the intervention documents we prepared for the district administration. But more than that, it is a snapshot of the people, the institutions, and the processes I worked with. I hope it will be useful not only to policy students like me but also to practitioners who are working in rural development and governance every day.

Why This Dissertation?

Jharkhand is a state of contrasts. It is rich in minerals, has major industries, and contributes to the national economy. Yet, it also carries some of the poorest social and livelihood indicators in the country. Saraikela Kharsawan, the district where I was posted, reflects this paradox. On one hand, it is home to the Adityapur Industrial Area, a cluster of automobile and manufacturing units that employ thousands. On the other hand, much of the rural population continues to depend on traditional farming, often without irrigation or access to markets.

This gap between industrial opportunity and agrarian stagnation shaped my experience and also the intervention I chose to design: an Agro Tech Park in Kuchai block. The idea was to create a space where farmers could see and learn modern practices, adopt new techniques, and add value to their produce. It was not just about technology, but also about giving people hope that farming could still be a dignified and profitable occupation.

What This Dissertation Tries to Do

The aim of this dissertation is to piece together my journey in a way that makes sense to others. Specifically, I want to:

| Research Question | Objective | Expected Outcome |

| Why is the adoption of modern agricultural practices low in Saraikela Kharsawan? | To diagnose structural, institutional, and behavioural barriers in farming. | Identification of key constraints such as weak extension services, limited awareness, and industrial pull factors. |

| How can a demonstration-based intervention encourage farmers to adopt new practices? | To design an Agro Tech Park as a training and demonstration hub. | Farmers exposed to modern methods have an increased willingness to experiment with high-value crops and allied activities. |

| What role can community institutions play in sustaining the intervention? | To strengthen the Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO) and involve SHGs. | Greater community ownership; improved collective marketing and governance. |

| How can convergence across departments support agricultural innovation? | To integrate Agriculture, Horticulture, Animal Husbandry, Fisheries, and JSLPS in the project. | Improved coordination, resource pooling, stronger institutional backing. |

| What lessons can inform policy for similar tribal-industrial districts? | To reflect on systemic challenges (funding volatility, bureaucratic transfers, and sustainability). | Policy insights on convergence, adaptive leadership, and embedding ownership in institutions. |

Table 1: Research Questions and Objectives Matrix

How I Have Written This – Methodology

This dissertation is based on a mixed qualitative practitioner-methods approach. Primary material comprises six quarterly reflection papers written during the fellowship, project documents such as the proposal, pitch deck, problem tree, result chain, and Gantt chart, and administrative records from the district, including Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO) registration details and training attendance lists. Supplementary information was gathered from informal interviews and discussions with farmers, Self-Help Group (SHG) members, FPO representatives, District Livelihood Coordination Committee (DLCC) members, and departmental officials. These interactions were documented in field notes rather than formal transcripts.

Analysis relied on triangulation: comparing administrative records, participant accounts, and direct observations from field visits to reconstruct the implementation process and assess outcomes. Quantitative evidence is limited and largely drawn from program records; qualitative insights are based on lived engagement with institutions and communities. The study does not attempt a counterfactual evaluation but instead presents a practitioner’s case study, capturing processes, adaptive learning, and system-level reflections that emerged during the intervention.

Structure of the Dissertation

The chapters follow the flow of the fellowship itself:

- Chapter 1: Introduction sets the stage and explains the purpose of this work.

- Chapter 2: District Overview paints a picture of Saraikela Kharsawan—its people, economy, and institutions—and shows why the intervention mattered.

- Chapter 3: Intervention Design explains how the Agro Tech Park was conceptualised, drawing from the problem tree, result chain, and proposal.

- Chapter 4: Intervention Implementation tells the story of how the plan unfolded, the milestones reached, and the difficulties faced.

- Chapter 5: Outcomes and Impact reflects on what changed for farmers, institutions, and systems, and what the limitations were.

- Chapter 6: Reflections and Learnings organises the key lessons into four categories: public institutions, community institutions, impact, and policy.

- Chapter 7: Final Reflection is a short personal note on my PPiA journey.

Why It Matters

Development in districts like Saraikela Kharsawan is not just about schemes and budgets. It is about people trying to make a life between farms, forests, and factories. It is about government officers, NGOs, self-help groups, and farmers all pulling in different directions, sometimes together, sometimes apart. By writing this dissertation, I want to show the human side of policy implementation—the struggles, the resilience, and the small successes that often get lost in official reports.

What I Took Away

Finally, this work is also about my own growth. Through the fellowship, I learnt how to listen to communities, how to navigate bureaucracies, and how to adapt when plans changed. I realised that interventions are not just technical fixes but social processes that require patience, negotiation, and trust.

This dissertation is therefore both a record of a project and a reflection on practice. It tries to capture the energy and complexity of working in a district administration, and the belief that small, thoughtful interventions can open up new possibilities for development.

District Overview

Introduction

Understanding the socio-economic and institutional landscape of a district is essential before designing and implementing any policy intervention. The effectiveness of a programme does not depend solely on its technical merit but also on how well it fits the realities of local demographics, livelihoods, governance, and culture. This chapter provides a profile of Saraikela Kharsawan district, where my Praxis PPiA Fellowship was based, situating the Agro Tech Park intervention within its wider developmental context.

Geography and Demographics

Saraikela Kharsawan was formed as the twenty-fourth district of Jharkhand, carved out of Ranchi, Khunti, and Chaibasa. The district has a varied geography, consisting of forested areas, rivers, and cultivable land alongside emerging industrial clusters. As per the Census of India (2011), the population was approximately 1.06 million, with a literacy rate of 68.85 per cent, slightly below the state average. Roughly 40 per cent of the population resides in the Adityapur Industrial Area Development Authority (AIDA) region, while the rest live in rural or semi-rural blocks.

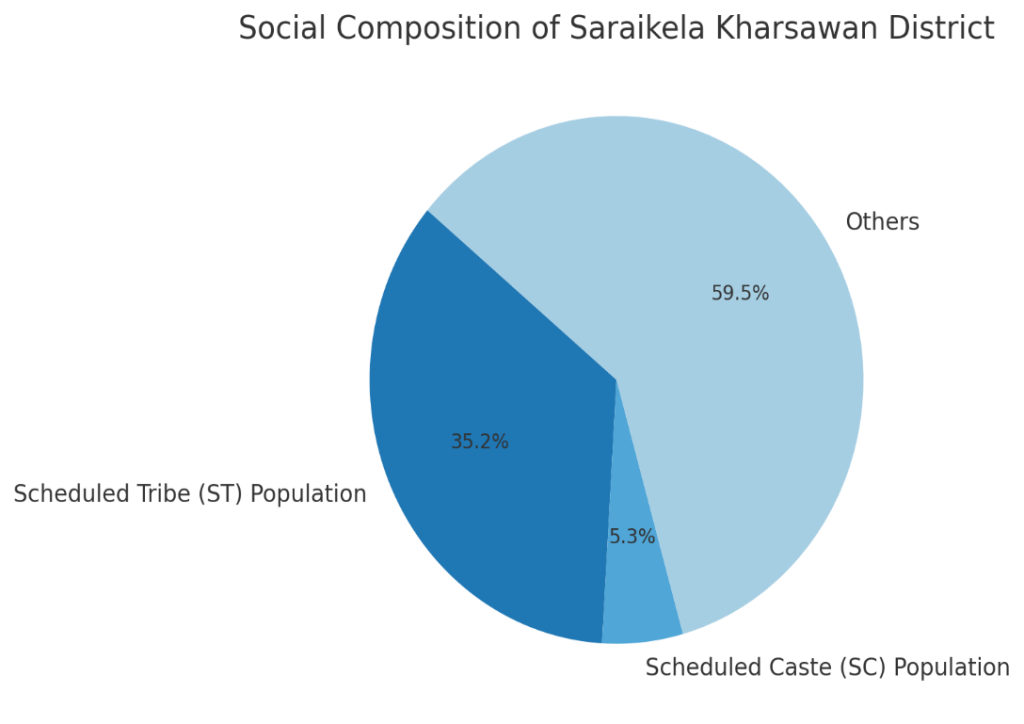

The district is socio-culturally diverse. Scheduled Tribes (STs) form a significant share of the population, alongside Scheduled Castes (SCs), Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and migrant workers from West Bengal, Bihar, and Odisha. Traditional communities such as the Mahto coexist with migrants, creating a mosaic of cultures, languages, and practices. While this diversity adds resilience, it also produces inequalities in access to opportunities. Migrants employed in Adityapur’s factories often earn modest but steady wages, while tribal households in remote villages depend on subsistence farming and forest resources.

Economic Landscape

Industry and Employment

Saraikela Kharsawan is among the few districts in Jharkhand where industry dominates the local economy. The Adityapur Industrial Area alone houses over 1,100 factories, employing more than 50,000 workers. Smaller clusters in other blocks add nearly 500 additional units, bringing industrial employment close to 100,000. Companies such as Tata Steel, Tata Motors, and BMW anchor this ecosystem.

Yet the industrial boom has not delivered prosperity for all. Many local and tribal workers are employed in lower-wage jobs with limited upward mobility. The availability of industrial employment also discourages youth from pursuing agriculture, leading to generational shifts away from farming even when wages in factories remain modest.

Agriculture and Livelihoods

Agriculture remains the mainstay for much of the rural population. Farmers primarily cultivate rice, pulses, and oilseeds, using traditional methods with little mechanisation or irrigation. Even though average landholdings are higher than in neighbouring districts such as Khunti, productivity remains low due to limited adoption of improved techniques like soil testing, integrated pest management, or drip irrigation.

Irrigation coverage is below 10 per cent, leaving most agriculture dependent on rainfall. Without storage or processing facilities, farmers have little incentive to diversify into high-value crops, further contributing to low incomes and migration to industrial or urban employment.

Non-Farm Livelihoods

Many households also depend on non-timber forest produce (NTFP) and informal wage labour. Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) in Chandil and Kuchai blocks — roughly 1,152 families — face extreme poverty and marginalisation. They rely heavily on forest produce, daily wage work, and government schemes. Limited education, healthcare, and secure land tenure further compound their vulnerability.

Social Institutions and Governance

Political Landscape

Saraikela Kharsawan plays an important role in Jharkhand’s political sphere. Prominent leaders such as Arjun Munda, Union Minister for Tribal Affairs, and Champai Soren, the Previous Chief Minister, hail from this district. While this visibility has brought attention, it has not always translated into consistent developmental progress. Political competition often shapes governance priorities, with a focus on short-term benefits over long-term capacity building.

Local Institutions

Governance operates through a mix of Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs), Self-Help Groups (SHGs), and Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs). Civil society actors and corporate foundations such as Tata Steel Foundation are also active. PRIs play a role in implementing programmes like MGNREGS and Amrit Sarovar, while SHGs focus on women’s financial inclusion. The FPO model is gaining ground as a means of aggregation and collective bargaining, though many remain institutionally weak.

Development Challenges

Despite the presence of multiple institutions, service delivery is uneven. Health facilities are scarce in rural areas, and education suffers from teacher shortages. In some blocks, the lingering effects of left-wing extremism (LWE) still restrict outreach. Though incidents of violence have declined, the legacy of insecurity continues to affect investment and mobility, particularly in Kuchai and Chandil.

Environmental Concerns

Rapid industrialisation has created environmental pressures, including air and water pollution, deforestation, and land degradation. At the same time, the Chotanagpur Tenancy (CNT) Act protects tribal land rights and restricts land transfers. Communities use this legal framework to resist displacement, creating tension between industrial expansion and conservation. This balancing act shapes development trajectories in the district.

Indicators of Development

Key indicators help provide a snapshot of the district’s developmental profile across sectors.

| Indicator | Value | Source |

| Population (2011 Census) | 1.06 million | Census of India, 2011 |

| Literacy Rate | 68.85% | Census of India, 2011 |

| Industrial Units (AIDA + other clusters) | ~1,600 | Govt. of Jharkhand, Industrial Profile (2015); Factory Inspectorate Report (2021–22) |

| Employment in Industries | ~100,000 | Industrial Profile; District Reports |

| Households Dependent on Agriculture | ~60% | District Statistical Handbook, 2022 |

| Irrigation Coverage | <30% | District Statistical Handbook, 2022 |

| PVTG Families (Chandil & Kuchai) | ~1,152 | District Administration Reports |

| Share of Scheduled Tribes in Population | ~35% | Census of India, 2011 |

| Health Infrastructure (PHCs per 1 lakh population) | Below the state average | District Health Profile, 2021 |

Table 2: Development Indicators of Saraikela Kharsawan

Relevance to the Intervention

The Agro Tech Park intervention was conceived as a direct response to the developmental paradoxes of Saraikela Kharsawan. Agriculture remained stagnant despite land availability, while youth gravitated toward industry. Farmers lacked exposure to modern practices due to weak extension services, and there were no integrated platforms to demonstrate innovative methods. The Agro Tech Park was designed to address these gaps by serving as a training and demonstration hub, showcasing diversified farming and linking it with institutional convergence. Its purpose was to rebuild confidence in agriculture as a viable livelihood, while providing a model for sustainability beyond external funding.

Intervention Design

Introduction

The Agro Tech Park (ATP) in Kuchai block emerged as a direct response to the agricultural stagnation of Saraikela Kharsawan. While industry had created jobs and drawn youth into wage employment, agriculture was struggling with low productivity, poor mechanisation, and limited diversification. Farmers remained dependent on rice, pulses, and oilseeds, cultivated using traditional methods. Irrigation was scarce, extension services weak, and exposure to modern practices minimal. The challenge was not only to improve productivity but to make agriculture meaningful and viable in a district where industry often overshadowed farming.

Problem Statement

The central problem was the low adoption of modern farming techniques. Farmers largely depended on paddy cultivation and lacked incentives to diversify. Industrial jobs attracted younger generations away from farming, while weak extension services and infrastructure gaps limited awareness of alternatives. Departments such as Agriculture, Horticulture, Animal Husbandry, and JSLPS operated in silos, with little convergence. This combination of traditional practices, weak institutional support, and industrial pull factors left agriculture stagnant, incomes low, and smallholders vulnerable.

Figure 4 Problem Tree Analysis

Theory of Change

The Agro Tech Park was based on a straightforward theory of change. It assumed that if farmers were exposed to modern agricultural techniques through live demonstrations, and if they received hands-on training in integrated farming systems, while institutions such as Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) and Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) were mobilised to provide ownership and market linkages, then farming would become more productive, incomes would rise, and agriculture would regain its viability as a livelihood.

Figure 5 Result Chain

Intended Beneficiaries

The intervention was designed to serve multiple layers of beneficiaries. The primary beneficiaries were small and marginal farmers in Kuchai block and adjoining areas, many of whom practised subsistence farming. Women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs) were secondary beneficiaries, gaining opportunities to engage in mushroom cultivation, poultry, and other allied activities. Institutionally, the registered Farmer Producer Organisation, which began with 150 members and was envisioned to expand to 750, was central to the model. The FPO was tasked with managing the park, ensuring ownership, and providing sustainability. At a broader level, systemic beneficiaries included the district administration and line departments, which could use the Agro Tech Park as a platform for convergence, training, and showcasing innovative practices.

Core Components of the Agro Tech Park

The Agro Tech Park combined crop diversification with allied sectors to reduce dependence on a single crop cycle. High-value crops such as dragon fruit, strawberries, and coloured cauliflower were introduced for their strong demand in nearby markets. Mushroom cultivation was developed as a quick-turnover activity particularly suitable for women’s groups. Jungle honey collection drew on forest resources in a sustainable way, while livestock units included goats, cows, buffaloes, and poultry, offering diversified income sources. Fish ponds demonstrated aquaculture techniques, broadening livelihood options. Together, these units created a circular farming system where waste from one activity could be reused in another.

Training and Capacity Building

Training was central to the Agro Tech Park’s design. A physical centre was set up to conduct non-residential training sessions, where farmers could learn by doing rather than listening passively. Topics included soil health management, crop diversification, integrated pest management, livestock disease prevention, and collective marketing through the FPO. These sessions were deliberately hands-on, using demonstration plots, livestock sheds, and ponds as classrooms. Women’s participation was especially notable in mushrooms and poultry, activities that could be managed alongside domestic responsibilities.

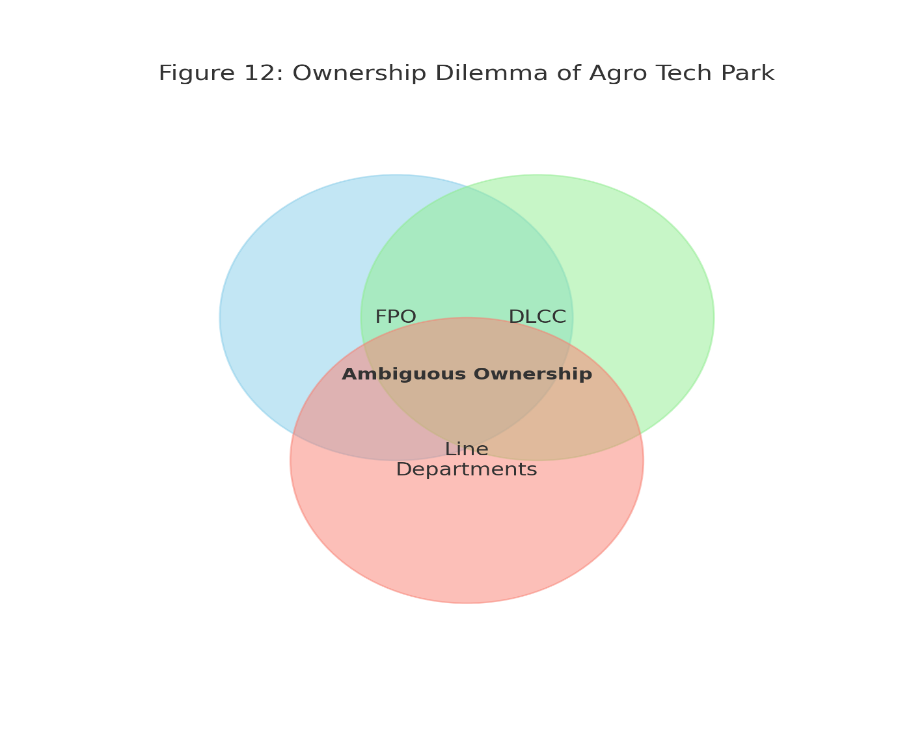

Implementation Architecture

Institutionally, the Agro Tech Park was anchored by the Farmer Producer Organisation. The FPO was responsible for managing assets, running operations, and marketing produce. Oversight was provided by the District Livelihood Coordination Committee (DLCC), chaired by the Deputy Commissioner, which brought together departments such as Agriculture, Horticulture, Animal Husbandry, and JSLPS. This architecture ensured that the project combined community ownership with administrative accountability.

Sustainability Plan

A critical design consideration was sustainability. The Agro Tech Park was structured to avoid long-term dependence on external funds by embedding revenue streams into the model. High-value crops were to be sold in nearby markets, livestock and fisheries marketed through FPO channels, and modest fees charged for farmer training. Convergence with schemes such as Mission Lakhpati Didi and JSLPS programmes was also built into the design. By placing the FPO at the centre of operations, the Agro Tech Park was expected to evolve into a self-sustaining, community-owned enterprise, reducing reliance on the district administration after the initial setup.

Anticipated Challenges

Even during the design stage, potential challenges were recognised. Funding volatility was a major risk due to reliance on Special Central Assistance (SCA) for LWE districts, as later proved when SCA was withdrawn. Bureaucratic hurdles in approvals and land acquisition were expected bottlenecks. Political pressures, including the risk of elite capture within the FPO, and resistance from farmers accustomed to traditional practices, also posed challenges. Finally, sustainability was uncertain, given the risk of losing administrative champions through transfers. Anticipating these risks informed the emphasis on convergence, FPO ownership, and diversified revenue.

| Component | Details |

| Problem Statement | Low adoption of modern agricultural practices in Saraikela Kharsawan; dependence on traditional crops (paddy, pulses, oilseeds); limited mechanisation and extension services; youth shifting to industry. |

| Theory of Change | If farmers are exposed to demonstrations and hands-on training in modern, integrated farming, and if institutions like FPOs are empowered with market linkages, then productivity will rise, incomes will diversify, and agriculture will regain viability as a livelihood. |

| Intended Beneficiaries | – Small and marginal farmers in Kuchai block.- Women SHGs (mushrooms, poultry).- Registered FPO with 150 members (target 750).- District line departments (for convergence and showcasing). |

| Key Activities | – Crop diversification (dragon fruit, strawberries, coloured cauliflower).- Allied activities (mushrooms, honey, livestock, fisheries).- Resource recycling (biogas, fodder reuse, poultry–fish integration).- Farmer training centre for demonstrations.- Strengthening FPO for ownership. |

| Intended Outcomes | – Higher adoption of modern agricultural practices.- Diversified household income streams.- Women’s economic participation.- Convergence across departments.- Sustainable, community-owned livelihood hub. |

Table 3 Intervention Design Summary

Conclusion

The design of the Agro Tech Park was ambitious yet grounded in local realities. It sought to revitalise agriculture in Saraikela Kharsawan by combining training, demonstration, and circular farming with institutional convergence and community ownership. By embedding sustainability features from the outset and anticipating risks, the intervention was positioned not only as a livelihood project but as a model for systemic change in a district caught between farms and factories.

Performance Framework

| Objective | Indicator | Baseline (2023) | Target (2025) | Data Source | Frequency |

| Farmer outreach | Number of farmers trained | 0 | 500 | Training attendance registers | Quarterly |

| Women’s participation | % of participants who are SHG women | 0% | 40% | JSLPS & training registers | Quarterly |

| Institutional strengthening | FPO membership count | 150 | 750 | FPO records | Half-yearly |

| Production outcomes | Value of sales from mushrooms, fish, honey (₹) | 0 | ₹10 lakh cumulative | FPO sales registers; haat records | Quarterly |

| Departmental convergence | Number of departments contributing resources | 0 | 4 | DLCC minutes; departmental reports | Half-yearly |

| Financial viability | % of operational costs met through FPO revenue | 0% | 60% | FPO accounts | Annual |

| Monitoring & oversight | DLCC meetings held on ATP progress | 0 | At least 4 per year | DLCC proceedings | Annual |

Table 4 PMF of Agrotech Park

Intervention Implementation

Introduction

Designing an intervention on paper is one challenge; translating it into practice within the complexities of a district administration is another. The Agro Tech Park (ATP) in Kuchai block moved from a proposal to an operating initiative during my fellowship, and this chapter narrates that transition. Implementation was shaped by both opportunity and constraint. While land was secured, infrastructure constructed, and training conducted, the process was also disrupted by shifting funding streams, bureaucratic changes, and political pressures. The following sections trace this journey, highlighting the milestones achieved, the bottlenecks faced, and the adaptations made.

Early Implementation Steps

The first stage involved identifying suitable land for the Agro Tech Park in Kuchai, a block previously affected by left-wing extremism. The land identified was publicly owned, but villagers used it as a pathway to the river and for cattle grazing. Resistance was voiced during initial consultations, and to resolve the issue, the district administration agreed to adjust the boundary of the park and construct an alternative pathway for community use. This compromise allowed the project to move forward without alienating the local population, while signalling that the intervention would be responsive to community concerns rather than imposed from above.

In parallel, the institutional framework for implementation was put in place. The Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO), which had been conceived in the design stage, was formally registered with 150 members. The FPO was envisioned as the backbone of the Agro Tech Park, with ownership of infrastructure, responsibility for day-to-day operations, and control over marketing. However, even during its formation, political actors attempted to influence leadership positions, raising concerns about elite capture. To ensure oversight and maintain transparency, the District Livelihood Coordination Committee (DLCC), chaired by the Deputy Commissioner, was tasked with monitoring progress and aligning departmental support. This dual structure of FPO ownership and DLCC supervision created a framework where both community participation and administrative accountability could coexist.

Physical Infrastructure Development

Once land and institutional frameworks were secured, construction of the core facilities began. Within the first year, goat sheds, cow sheds, mushroom cultivation rooms, fish ponds, and storage sheds were completed. These facilities were designed to serve as demonstration units rather than large-scale production hubs, showing farmers how integrated farming systems could be set up within modest landholdings.

Equally important was the integration of components. Poultry waste was channelled into fish ponds as feed, while animal dung was used in biogas plants to power small greenhouses. Crop residues were recycled as fodder. These linkages, though modest in scale, embodied the circular farming model envisioned in the design stage. Farmers initially viewed these systems with scepticism, but seeing waste converted into useful resources during site visits generated interest and confidence.

Capacity Building and Training

Training farmers was central to the Agro Tech Park’s purpose. The first three-day non-residential training was conducted with 77 participants, covering soil health management, crop diversification, integrated pest management, livestock care, and collective marketing through the FPO. These sessions were deliberately practical, conducted within the demonstration plots and livestock units so farmers could observe techniques directly rather than rely on lectures.

The training also brought in a strong gender dimension. Women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs) took particular interest in mushroom cultivation and poultry management, activities that could be pursued without requiring large landholdings. Their involvement aligned the Agro Tech Park with Mission Lakhpati Didi, the state’s flagship women’s livelihood programme, and created space for women to play a more central role in farming-related enterprises.

Financial Architecture

The financial backbone of the Agro Tech Park was initially the Special Central Assistance (SCA) for Left-Wing Extremism (LWE) affected districts. An overall budget of three crore rupees had been projected, with fifty lakh rupees sanctioned for agricultural components. However, midway through implementation, the Government of India withdrew SCA support on the grounds that Saraikela Kharsawan no longer qualified as an LWE district. This decision had immediate consequences, sharply reducing available funds and threatening to stall the project.

In response, the district administration and FPO had to adapt quickly. Convergence with line departments was accelerated, with the Agriculture Department providing seeds, the Horticulture Department supporting plantations, and Animal Husbandry contributing livestock units. The possibility of tapping corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds from nearby industries such as the Tata Steel Foundation was also explored. Meanwhile, the FPO was encouraged to begin early revenue generation by selling mushrooms, honey, and fish in weekly haats. These measures did not fully replace the withdrawn funds but kept the project afloat and demonstrated its resilience in the face of volatility.

Administrative and Political Dynamics

Implementation also revealed the fragility of bureaucratic continuity. Key officers who had supported the Agro Tech Park were transferred during the course of the fellowship, and their successors did not always share the same commitment. Each transfer required fresh rounds of advocacy, presentations, and explanations to ensure the project remained on the district agenda. In many ways, the fellow’s role became one of policy entrepreneurship—keeping the project visible to senior officials, drafting progress updates, and ensuring that momentum was not lost.

Political pressures were equally present. Local elites attempted to exert influence over the FPO, sometimes leading to disagreements among members. The DLCC had to step in on several occasions to restore confidence and reinforce the principle of collective decision-making. These dynamics slowed progress but also underscored the importance of institutional safeguards against elite capture.

Community Mobilisation

Despite early scepticism, farmer participation gradually grew as visible results emerged. Mushrooms harvested in the park and sold in haats, fish caught from demonstration ponds, and honey bottled for local markets gave credibility to the intervention. These outcomes persuaded more farmers to join the FPO, which began moving towards its target of 750 members.

The diversity of engagement was notable. Women’s groups were most active in mushrooms and poultry, while younger farmers showed interest in horticulture. This generational and gender balance strengthened the intervention by spreading ownership across different community segments.

Monitoring and Review Mechanisms

Monitoring was conducted through regular DLCC meetings, where departmental contributions were reviewed and bottlenecks addressed. A dashboard was also proposed to track infrastructure, training numbers, and revenue, though it remained only partially functional by the end of the fellowship. Transparency was maintained through quarterly progress reports to the district administration, which not only recorded achievements but also flagged challenges such as funding gaps or delays in departmental contributions.

4.9 Key Milestones Achieved

By the close of the fellowship period, the Agro Tech Park had completed several milestones. Infrastructure was in place, including livestock sheds, fish ponds, and mushroom cultivation rooms. The first training cycle had reached 77 farmers, with strong participation from women’s groups. Pilot production cycles of mushrooms, honey, and fish had demonstrated commercial viability, with produce sold in local haats. The FPO had begun expanding its membership base, and departmental convergence, though uneven, had been initiated through contributions from Agriculture and Animal Husbandry.

In the final implementation phase, additional developments took shape. A district-level convergence committee was established to provide stronger oversight and align departmental support, while the Deputy Commissioner ensured the Agro Tech Park remained visible in review meetings. New plans were drawn up to issue Expressions of Interest (EOIs) to bring NGOs and private FPOs into the initiative, aiming to strengthen technical support and marketing. At the same time, setbacks were also encountered. A mortality incident in the goat unit highlighted gaps in veterinary support and underlined the fragility of livestock-based interventions without consistent technical backup. These challenges served as reminders that physical infrastructure alone does not guarantee sustainability; institutional and technical systems must also evolve in tandem.

| Milestone | Planned Timeline | Status | Notes |

| Land Identification & Demarcation | Q1 | Achieved | Adjusted after community consultations; a separate walkway was constructed for villagers. |

| FPO Registration | Q1 | Achieved | Registered with 150 members; expansion to 750 targeted. |

| Construction of Goat Sheds, Cow Sheds, Mushroom Rooms, Fish Ponds | Q2–Q3 | Achieved | Structures completed as demonstration units. |

| First Farmer Training (3-day, non-residential) | Q3 | Achieved | 77 farmers trained; strong women’s participation in mushrooms and poultry. |

| First Production Cycle (Mushrooms, Fish, Honey) | Q4 | Achieved | Produce sold in local haats; established commercial viability. |

| Convergence with Line Departments | Q2–Q5 (Ongoing) | Partial | Agriculture and Animal Husbandry contributed; others less consistent. |

| Dashboard for Monitoring & DLCC Reviews | Q5 | Partial | Proposed and discussed; not fully functional. |

| Expansion of FPO Membership (Target: 750) | By Q5 | Partial | Membership reached ~600 by fellowship end. |

| Formation of the Convergence Committee | Q6 | Achieved | A committee was created to strengthen oversight and departmental coordination. |

| Expression of Interest (EOI) for NGO/FPO Partnerships | Q6 | Initiated | Plans were developed to onboard external partners for technical and marketing support. |

| Goat Mortality Incident | Q6 | Challenge | Highlighted gaps in veterinary care and the risks of livestock-based interventions. |

| Visibility of Kuchai Block | Q6 | Achieved (Unintended) | ATP brought administrative attention; high-mast lights benefited the local school and CHC. |

Table 5 Milestone Planned vs Achieved

Outcomes and Impact

Introduction

The Agro Tech Park (ATP) in Kuchai was not only a designed intervention but also an experiment in practice. Beyond its infrastructure and activities, the real test lay in its ability to change lives and institutions. This chapter examines the outcomes that emerged during the fellowship period, both tangible and intangible, at the household, community, and systemic levels. It also reflects on the adaptive challenges encountered, the lessons for scalability, and the long-term prospects for sustainability. Measuring impact within the relatively short duration of implementation is difficult, yet early patterns reveal valuable insights into how such an intervention might evolve in the future.

Household-Level Outcomes

The most immediate effects were seen at the household level. The first cycles of mushroom cultivation, honey collection, and fish rearing demonstrated commercial viability and brought modest income gains to participating families. Farmers who sold mushrooms in local haats or who harvested fish from the demonstration ponds reported that even these small earnings were meaningful, especially as they came from activities that were previously unfamiliar to them.

Knowledge and skills also improved through the training programs. Farmers who attended the three-day sessions gained practical exposure to soil health management, crop diversification, livestock care, and pest control. For many, this was their first structured encounter with modern agricultural practices. Women participants, in particular, expressed appreciation for mushroom and poultry training, which they could integrate into their daily routines without requiring large landholdings. These experiences began to shift attitudes toward agriculture. Farmers who were initially sceptical about “new methods” grew more open to experimentation once they saw positive results in the field.

Community and Institutional Outcomes

At the community level, the Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO) expanded its membership base, moving towards the target of 750 farmers. Although challenges remained in governance and participation, the fact that farmers were willing to join and contribute marked progress in building collective platforms. The FPO also began assuming its role in marketing produce and reinvesting small profits into operations, steps that strengthened its institutional identity.

Women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs) engaged with the Agro Tech Park in ways that extended beyond savings and credit. Their involvement in mushroom cultivation and poultry units created new livelihood avenues and increased their confidence in participating in farming decisions. This link between SHGs and the ATP helped reinforce women’s role in household and community-level income generation.

The District Livelihood Coordination Committee (DLCC) served as another important institutional outcome. While departments often worked in silos, the DLCC created a space for periodic reviews and coordination. Agriculture and Animal Husbandry departments contributed resources such as seeds and livestock, while the Horticulture department supported plantations. Though convergence was uneven, the mechanism demonstrated that departmental alignment could be fostered if deliberate structures were put in place.

During the final phase, a multi-stakeholder convergence committee was constituted by the district administration to coordinate departmental contributions and monitor the Agro Tech Park. This committee improved oversight, revived district attention on the FPO, and signalled a gradual shift from individual champions to collective governance structures.

Systemic and Adaptive Challenges

The withdrawal of Special Central Assistance (SCA) funds for left-wing extremism affected districts disrupted the financial foundation of the Agro Tech Park. This exposed the fragility of projects dependent on a single funding source. Adaptive leadership was needed to pivot toward departmental convergence, CSR partnerships, and early revenue generation by the FPO. While these measures did not fully cover the gap, they kept the project operational and demonstrated resilience.

Bureaucratic discontinuity also posed challenges. Frequent transfers of key officials meant that momentum had to be rebuilt repeatedly. Each new officer had to be briefed, persuaded, and engaged to ensure that the Agro Tech Park remained on the district agenda. This constant advocacy highlighted the difficulty of sustaining innovations that are not yet institutionalised. In Quarter 6, a goat mortality incident underscored the fragility of livestock-based interventions without adequate veterinary support. This setback highlighted the need for technical backstopping and revealed how reliance on livestock requires stronger institutional systems. It also illustrated the importance of persistence, since continued advocacy was necessary to keep the project on track despite such challenges.

Ownership and sustainability remained contested. Departments viewed the ATP as an additional burden rather than part of their core mandate, while the FPO was still developing its managerial capacity. Political pressures further complicated governance, with local elites seeking to influence decisions.

Unintended Outcomes

Beyond its planned activities, the Agro Tech Park also produced unintended outcomes. The installation of high-mast floodlights near the site improved safety and benefitted a nearby school and Community Health Centre, enhancing local infrastructure. In addition, the project brought renewed administrative attention to Kuchai block, an area long associated with left-wing extremism. The Agro Tech Park’s presence gave the block visibility in district-level planning, reframing it as a site for innovation rather than neglect

Evidence of Scalability

Despite these challenges, the Agro Tech Park showed signs of scalability. The demonstration effect was strong: once farmers saw mushrooms and fish being sold successfully, interest in joining trainings and the FPO increased. The model also aligned with existing policies such as Mission Lakhpati Didi and national-level schemes on livelihood diversification, creating policy resonance. Comparable initiatives such as Kisan Pathshalas in Khunti and Uttar Pradesh demonstrated that training-based interventions could scale when embedded into government systems. However, scalability would depend on whether the Agro Tech Park could secure operational costs, institutionalise ownership, and build reliable market linkages beyond weekly haats.

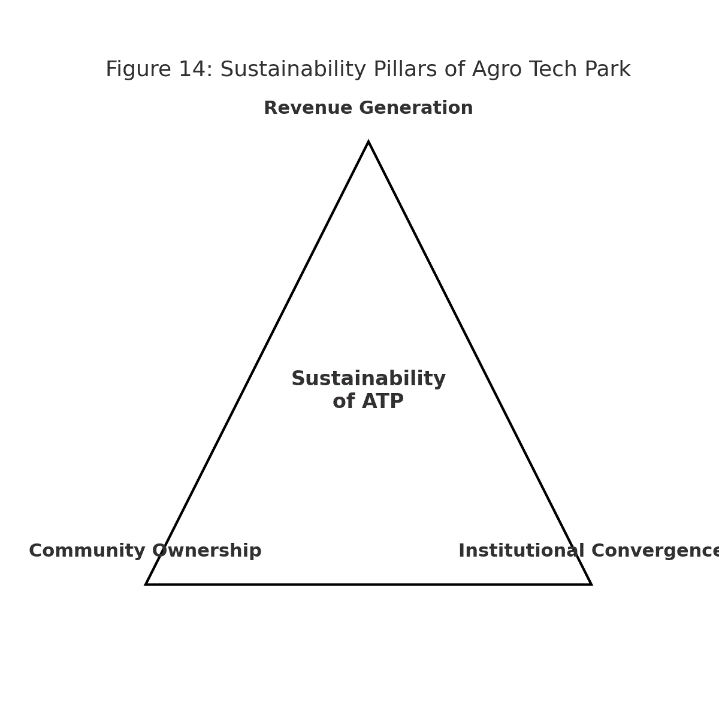

Long-Term Sustainability

The sustainability of the Agro Tech Park rests on three pillars: revenue generation, institutional convergence, and community ownership. Revenue must flow consistently from the sale of crops, livestock, and fisheries to cover operational expenses. Convergence is required so that departments view the ATP as a platform to deliver their schemes rather than as an external project. Finally, community ownership, through the FPO and SHGs, is essential to maintain energy and accountability. Each of these pillars carries risks—market fluctuations, weak departmental commitment, or elite capture—but strategies exist to mitigate them, such as diversification of products, formalising departmental roles, and strengthening FPO governance.

| Pillar | Description | Risks Identified | Mitigation Strategies |

| Revenue Generation | Income from the sale of high-value crops, livestock, fisheries, and mushrooms through the FPO. | Market fluctuations, low initial volumes, and disease outbreaks in livestock. | Diversify products; secure forward linkages with urban markets; maintain reserve funds. |

| Institutional Convergence | Contributions from Agriculture, Horticulture, Animal Husbandry, JSLPS, and oversight by DLCC. | Reluctance of departments to commit resources; weak accountability. | Formalise departmental roles via MOUs; schedule regular DLCC reviews; align activities with state schemes. |

| Community Ownership | Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO) and SHGs to manage operations and assets. | Elite capture, weak governance capacity, and low participation of marginal farmers. | Strengthen FPO leadership skills; ensure transparency in decision-making; build inclusive membership. |

Table 6: Sustainability and Mitigation

Reflections and Learnings

Introduction

The Praxis PPiA Fellowship was not only about designing and implementing an intervention but also about cultivating the ability to reflect on what these processes revealed. The Agro Tech Park in Saraikela Kharsawan provided lessons across multiple levels — from public institutions and community dynamics to questions of impact and policy. These reflections, although organised into typologies here, were often interconnected in practice, shaped by the constant negotiation between design, implementation, and adaptation.

Public Institution Learning

One of the clearest lessons concerned the fragility of bureaucratic continuity. Key officers who had supported the Agro Tech Park were transferred, and their successors often arrived with different priorities. Each transfer required new rounds of advocacy to keep the intervention on the district’s agenda. This experience underscored how dependent many innovations are on individual champions rather than institutionalised processes. Sustainable change requires embedding ownership in systems rather than relying solely on the commitment of particular officers.

Another important learning was about convergence. While it was frequently invoked in official documents, achieving it in practice proved far more challenging. Departments tended to operate in silos, each focused on its own schemes. The DLCC offered a mechanism for bringing them together, but it needed constant nudging by senior officials to be effective. This highlighted the need for deliberate orchestration rather than assuming that convergence would happen naturally.

The final phase of the Agro Tech Park reinforced another institutional lesson: many initiatives fall into a ‘grey zone’ where no single department feels complete ownership. While the convergence committee helped reduce this risk, the lack of a designated lead department continued to affect accountability. This highlighted the need for clearer institutional anchoring in future interventions.

I also came to appreciate the role of advocacy. My position as a fellow gave me no formal authority, yet I found that regular updates, strategic reminders, and timely interventions could keep the project visible to decision-makers. This revealed that district-level innovation often requires policy entrepreneurship — the ability to mobilise interest, maintain momentum, and sustain attention even when institutions are otherwise fragmented.

Community Institutions Learning

The Farmer Producer Organisation, which lay at the heart of the Agro Tech Park, became a powerful learning site. Its registration and early activities demonstrated the potential of collective platforms, but it also exposed the risks of political interference. Local elites sought to capture leadership positions, slowing decision-making and creating tensions. This taught me that FPOs cannot be treated as neutral spaces; they need safeguards, capacity building, and transparent processes if they are to genuinely serve farmer interests.

Women’s Self-Help Groups offered a more hopeful lesson. Their involvement in mushroom cultivation and poultry units created new livelihood opportunities and strengthened their role in farming decisions. For many women, these were their first steps beyond savings-and-credit activities, and they quickly took ownership of income-generating processes. This reinforced the importance of designing interventions with entry points that align with women’s realities. When opportunities are both practical and accessible, SHGs can move from being peripheral actors to central players in community development.

Trust was another significant learning. Many farmers were initially sceptical about the Agro Tech Park. It was only after they saw mushrooms being sold or fish being harvested that their attitudes began to shift. This showed that behavioural change is less about persuasion and more about demonstration. Communities are more likely to adopt new practices when they can witness tangible benefits themselves.

The Quarter 6 experience also revealed how setbacks, such as the goat mortality incident, tested the community’s confidence. While initially discouraging, the FPO’s ability to continue operations and maintain farmer engagement demonstrated resilience. It showed that trust is not only built through early successes but also sustained through honest acknowledgement of failures.

| Aspect | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Membership Base | Registered with 150 members; steady growth towards 600 members. | Target of 750 not achieved within the fellowship period; slow mobilisation in remote villages. |

| Operational Role | Managed sales of mushrooms, honey, and fish in local haats, showing early viability. | Limited managerial and financial literacy among leaders; dependence on external facilitation.The shock of many deaths of goat is also one of the weaknesses. |

| Governance | Democratic registration process with farmer representation. | Political interference and risk of elite capture; decision-making sometimes delayed. |

| Market Linkages | Access to weekly haats and potential markets in Jamshedpur and Ranchi. | Lack of formal contracts; weak integration with wider value chains. |

| Community Perception | Farmers began to see the FPO as a platform for collective action. | Trust issues persisted among some smallholders; uneven participation of marginalised groups. |

Table 7 Strengths and weaknesses

Impact Learning

At the level of impact, one important insight was that small wins matter. While the income gains from the first production cycles were modest, they signalled that agriculture could, in fact, generate returns if modern practices were adopted. These early successes helped change perceptions and encouraged more farmers to consider joining the FPO or participating in training.

Sustainability emerged as another critical area of reflection. The sudden withdrawal of SCA funds showed that sustainability cannot be guaranteed by design alone. Instead, it has to be renegotiated continuously as circumstances change. The project survived by drawing on departmental convergence, CSR contributions, and FPO-led revenue, but these measures had to be actively cultivated. Sustainability, therefore, is not a static feature of interventions but a dynamic process that requires ongoing attention.

Finally, questions of scalability became apparent. The Agro Tech Park aligned well with state and national policies such as Mission Lakhpati Didi and Kisan Pathshala models in other districts. This alignment created space for replication. Yet, scaling is not simply about copying; it is about embedding successful elements into government systems so that they become routine practice rather than isolated pilots.

Policy Learning

Policy-level reflections also emerged from the Agro Tech Park experience. Funding volatility was the first lesson. The withdrawal of SCA support, based on broad LWE indicators rather than ground realities, disrupted an intervention that was beginning to show results. This demonstrated how top-down decisions can undermine local initiatives and underscored the need for buffer mechanisms, such as contingency funds, to protect ongoing projects from sudden policy shifts.

Another area of learning was the importance of adaptive leadership. Without formal authority, I had to navigate between departments, mobilise the FPO, and keep senior officers engaged. This experience showed that technical solutions alone are insufficient. Development work in complex environments requires the ability to mobilise people, reframe challenges, and lead without authority. Another important insight from the final phase was the role of bureaucratic nudging and persistence. Even when the Agro Tech Park risked fading from administrative attention, consistent follow-ups and reminders ensured that it remained on the district’s agenda. This reflects a broader policy lesson: successful implementation often depends less on grand strategies and more on the steady, everyday work of keeping initiatives visible and relevant.

The broader implication of these reflections is that tribal-industrial districts like Saraikela Kharsawan demand policies that balance industry and agriculture. Interventions must recognise that industrial jobs will continue to attract youth, but agriculture can remain viable if it is diversified, modernised, and linked to markets. This suggests that livelihood policies for such districts should not attempt to preserve agriculture in its traditional form but instead transform it into a complementary livelihood pathway.

Beyond the Four Typologies

While the four categories of learning — public institutions, community institutions, impact, and policy — provide a useful framework, two cross-cutting insights also stood out. The first was the role of trust. Development is as much relational as it is technical. Building trust with farmers, SHGs, and officials was essential to creating space for collaboration and change. The second was the role of reflexivity. The process of writing quarterly reflections forced me to step back from daily activities and make sense of them. This structured reflexivity helped me adapt strategies in real time and deepened my learning.

References

- Census of India (2011). Primary Census Abstract. New Delhi: Government of India.

- Centre for Science and Environment (2019). State of India’s Environment Report. New Delhi.

- Corbridge, S. (2004). Jharkhand: Environment, Development and Ethnicity. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Down to Earth (2024). “Lack of irrigation facilities affects Jharkhand farmers.”

- Factory Inspectorate, Saraikela Kharsawan (2021–22). Annual Report. Government of Jharkhand.

- Financial Express (2019). “Kisan Pathshala for Doubling Farmers’ Incomes.”

- Govind, P. (2017). “Education and Marginalised Communities in Jharkhand.” Economic and Political Weekly, 52(33).

- Government of Jharkhand (2015). Industrial Profile of Saraikela District. Ranchi.

- Kujur, R. (2019). “Politics of Tribal Identity in Jharkhand.” Social Change, 49(2): 227–242.

- Live Hindustan (2023). “CM inaugurated Karra Kisan Pathshala.”

- Mitra, S. (2022). “The Decline of Left-Wing Extremism in Jharkhand: Implications for Development.” Journal of Asian Security Studies, 14(1).

- Planning Commission (2013). Evaluation Study of MGNREGS in Jharkhand. New Delhi.

- Prasad, A. (2010). “Transformation of Tribal Society through Proto-Industrialisation: A Case of Jharkhand.” Economic History Review, 8: 3953–3971.

- Shah, A. (2010). In the Shadows of the State: Indigenous Politics, Environmentalism, and Insurgency in Jharkhand. Durham: Duke University Press.

- World Bank (2020). Transforming Agriculture in Eastern India. Washington DC.

- World Health Organization (2021). World Health Statistics. Geneva.

Xaxa, V. (2018). State, Society and Tribes: Issues in Post-Colonial India. New Delhi: Pearson.