Introduction

I am placed as a Public Policy in Action (PPIA) Praxis Learner in Simdega district, Jharkhand, where I have had the unique opportunity to closely engage with both the District Administration and the local communities. This placement has enabled me to understand the lives and aspirations of the people while simultaneously contributing to developmental governance at the grassroots level. Over the course of my fellowship, I was exposed to the livelihood, educational, and healthcare ecosystems within the district. Actively engaging with these systems allowed me to appreciate the multidimensional challenges of development and the opportunities that emerge from within these systems, through a collaborative approach.

My two-year journey in Simdega has been a meaningful learning experience. It has given me the chance to work across multiple workstreams, including theory, practical and programmatic aspects of the development sector, and to appreciate my field of work. The opportunity to extend strategic support to the District Administration was an enriching experience for me. Working closely with senior officials, including the Deputy Commissioner, Deputy Development Commissioner, and other district- and block-level officers, enabled me to gain firsthand insights into governance processes, administrative structures, and the policy implementation ecosystem. This professional engagement expanded my understanding of institutional systems but also enhanced my ability to contribute meaningfully to local governance.

Equally important was my interaction with the rural communities of Simdega. By working with and for these communities, I was also able to understand and experience the lives and aspirations of rural India. This engagement, with both the administration and the people, gave me a holistic perspective of development, where policy design and community realities intersect. I also consider myself fortunate to have contributed to the design of developmental projects in close collaboration with the district administration, projects that directly impact and improve the lives of people.

One of the most significant highlights of my fellowship was the design and implementation of my intervention, which focused on enhancing lac-based livelihoods in Simdega. Lac cultivation is a traditional practice in the region and holds significant untapped potential for strengthening local livelihoods. I designed an intervention aimed at integrating lac cultivators into a more sustainable and profitable value chain. The major idea was to encourage year-round cultivation of lac by promoting the adoption of scientific techniques and best practices. As part of this initiative, I worked to link farmers from selected cooperatives with structured scientific training programmes, ensuring that they had access to updated knowledge and improved cultivation methods. In collaboration with SIDHKOFED, farmers were also provided with high-quality seed and toolkits, which are reusable assets for multiple production cycles. These interventions helped build the scientific capacity of lac cultivators and laid the groundwork for a more consistent and enhanced livelihood portfolio.

While lac cultivation showed promising results, the challenge of processing emerged as a critical bottleneck. Although the intention was to ensure that the produced lac could be processed within the district, the large-scale processing unit envisioned for this purpose has faced initial hurdles in its establishment. Addressing these challenges and facilitating the revival of this processing facility has since become a central focus of my efforts, as it holds the key to adding value to local produce and improving farmers’ incomes.

In the chapters that follow, I will present a structured account of my intervention journey. Chapter 2 provides an overview of the district, offering geographical and contextual background relevant to the intervention. Chapter 3 details the intervention design, beginning with the identification of the core problem and outlining the design framework along with the challenges encountered during its formulation. Chapter 4 shifts focus to intervention implementation, describing the sequence of activities undertaken and the on-ground challenges faced during execution. Chapter 5 highlights the outcomes and impacts of the intervention while also discussing the sustainability plan developed to ensure continuity beyond the fellowship period. Chapter 6 reflects on the key learnings I gained from the process, categorized across four major typologies of learning. Finally, Chapter 7 concludes with my reflections on the overall experience of being part of the Public Policy in Action Praxis Residency Programme, summarizing how it has shaped my professional journey and deepened my understanding of development practice.

District Overview

The Place:

Simdega district is located in the south-western part of Jharkhand, situated in the South Chotanagpur Division of the state. The district was formed on 30 April 2001 being carved out from Gumla district. Simdega shares inter-state borders with Odisha and Chhattisgarh; this factor plays an important role in the culture and economy of the district. The district comprises 10 Development Blocks, namely Bano, Jaldega, Kurdeg, Bolba, Simdega, Kolebira, Pakatanr, Kersai, Bansjor, and Thethaitangar. There are 94 Gram Panchayats and 451 villages in the district. Simdega has a total area of 3761.20 km2; 56.82 % of the total area is plateau region, which covers around 2137.24 km2, 1299.06 km2 area is hilly terrain which accounts to 34.54 % of the area of the district, and only 180.46 km2, which accounts for 4.79 % of the total district area, is plain surface.

According to the ‘Ground Water Information Booklet: Simdega District, Jharkhand’, the Chotanagpur plateau, wherein the district is positioned, is a region of large physical inequalities and presents a rich panorama of topographical features. The general configuration of the region varies from valley fills, peneplains, to structural ridges. In the district, three well-marked erosion surfaces are evident. Soils in Simdega district have formed as a result of in-situ weathering of crystalline rock (granite & gneisses), climate, topography, and vegetation have contributed to the formation of soils in the area. The district is mainly a dissected upland of ancient crystalline rocks, which covers the major parts of the district. Groundwater availability in crystalline rocks is considered to be poor because of the absence of primary porosity, which is essential for the free occurrence and movement of groundwater. The secondary porosity in the form of fractures, fissures, joints, etc. develops due to orogenic movements aided by weathering, making the crystalline rocks a potential repository for the occurrence and movement of groundwater.

The district is forming the Sankh sub-basin of the Brahmni basin. The river Sankh is the main river of the district, which flows from north to south in the western part of the district. The tributaries of the river Sankh are the Palamara, Girma, Chhinda, Lurgi and Dev Rivers. The other important river of the district is the river South Koel, which forms the eastern boundary of the district. The river South Koel flows from north to south and finally joins the river Sankh in Odisha state. All these drainages are characterized by rapid surface run-off and are seasonal in nature. The drainage pattern of the district is dendritic. These topological diversities peculiar to the region contribute both positively and negatively to the daily lives of the people residing here; while some regions have good irrigation facilities, some regions experience challenges with respect to the availability of irrigation facilities. Most farmers depend on wells, but these are often unreliable because the land is rocky. Where ponds or small streams store water, people mainly grow vegetables, and summer paddy is cultivated only in a few low-lying areas.

Simdega experiences a healthy climate throughout the year. Normal atmospheric temperature in the area often goes up to 42 °C in summer and it goes down to about 4 °C during winter. The average annual rainfall of the district is 1487 mm. Rainfall is the only source of replenishment of groundwater in the district.

To consider the agricultural profile of the district, as per statistics, only 4669.83 hectares out of 134024 hectares of cultivable land are irrigated. Agriculture mainly depends on monsoons. Even though the average annual rainfall is 1100-1200 mm, the lack of an effective rainwater harvesting system leaves most of the rainwater unutilised. The district depends heavily on seasonal and rain-fed agriculture and a largely single-crop cycle. The major crops being cultivated in the district are cereals, including rice, wheat, and maize; pulses like black gram, chick pea, etc., vegetables and fruits like potato, tomato, brinjal, lady’s finger, chilli, cauliflower, papaya, guava, blackberry, mango, etc.

Simdega is renowned for being a leading producer of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) as well. Lac, tendu leaves, mahua, harda, behda, sakhua, and tamarind are produced in the district on a major scale and are exported to other states. NTFP availability and market are seasonal activity. The district also has favourable conditions for tasar rearing, lac processing industries, timber industry, handicrafts, etc.

The People

Simdega is the third least populous district of the state. The district is placed 20th in the state with regard to the decadal population growth rate of 16.62%. Simdega exhibits a population density of 160/km2. The population of the district, according to the 2011 Census, is 5,99,578. The urban population comprises about merely 7% of the total population, which is a very small section with respect to the total number of inhabitants of the district. This also implies that a majority of people residing in the district belong to rural areas.

The tribal population of the district, being more than 70%, encompasses a major section of the populace. The major caste subgroups prevalent in the district are Bhogta, Ghasi, Bhuiyan, Turi, Dom (Dhangad), Bauri, and Kanjar, and the major tribe subgroups are Munda, Kharia (Dhelki/Dudhad), Oraon, Gond, and Lohra. Birhor and Korwa are the Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) existing in the district; their total population would range from 600 to 650 individuals. Christianity is the religion practiced by a majority of the population, which makes Simdega a Christian-majority district in the country, other than the districts in the North-East. The languages spoken in the district, apart from Hindi, are Sadan/Sadri, Mundari, Kharia, Nagpuria, Kurukh/Oraon, Urdu, Odia, Bhojpuri, Magadhi/Magahi, and others. Simdega, with its predominantly tribal and Christian population, has cultural practices and traditions that stand distinct from other parts of Jharkhand. The tribal communities here enjoy a level of empowerment comparable to the wider rural population. In my view, the empowerment in rural Simdega is not shaped by caste, religion, or sectarian differences; instead, the key divide arises from geography, specifically, the rural–urban gap and challenges of inaccessibility.

Simdega is a district with an unmatched Sex Ratio of 997, which surpasses the average national sex ratio of 940 females per 1000 males. The literacy rate of the population is 67.59% which is almost at par with that of the state of Jharkhand. The district-level literacy rate for Scheduled Tribe females is higher than the state-level figures. The female literacy rate of Simdega is lower than the male literacy rate, but higher than the state’s average. The urban literacy rate is higher for both males and females, with the majority of the population being rural inhabitants. Additionally, women in the region are actively engaged in community initiatives.

Similar to other rural districts in the country, agriculture is the main source of income for the rural parts of the district. However, agriculture is practiced in a very primitive and underdeveloped manner in the district. The majority of the rural populace depends on traditional methods of production without being aware of the scientific advancements. Other concerns of the sector include lack of irrigation facilities, the absence of scientific inputs, poor marketing facilities, underdeveloped infrastructure, etc. Apart from this, people residing in certain remote regions of the district find difficulty in accessing services and facilities, in addition to the challenge they face in travelling. The lack of opportunities within the district is another major challenge faced by the community, because of which they are forced to migrate to cities primarily for menial, unskilled labour. The district was also unpopular for a history of human trafficking and Left-Wing Extremism that was prevalent in the district, but has undergone a considerable reduction lately.

Besides agricultural activities, animal husbandry and small-scale food processing cottage industries are another major source for the communities to sustain their livelihoods. They avail credits provided through collectives like SHGs, being linked to government institutions like JSLPS (Jharkhand State Livelihood Promotion Society). The people here are active and ambitious. They, especially the women here, are ready to take up any challenge to improve their lives. But, many times, they fail to sustain the initiatives they have taken up, mainly due to the lack of a systematic and scientific approach. I have also observed that, despite the failures they had faced in the past, they are not ready to quit. The communities here hold a firm grip on their culture; they are proud to celebrate and exhibit their traditional art forms, clothing, and festivities in the most authentic way possible. The fabric of culture is intricately woven into the lives of the people here.

Simdega is also known as the “Cradle of Hockey in Jharkhand”. There are a number of hockey players from the district who have grown to be the pride of the nation; Asunta Lakra, Salima Tete, Deepika Soreng, and Beauty Dungdung are to name a few from the list.

The Institutions

The network of healthcare, education, and sanitation systems is well-established in the district, but the effectiveness of the functioning of the institutions within these systems is questionable. In some cases, lack of human resources becomes a challenge in the remotest belts of the district, whereas in certain other cases, the lack of proper infrastructure becomes the major drawback.

To consider the healthcare system of the district, there are 7 Health Blocks established, comprising the 10 Developmental Blocks. The District Hospital or Sadar Hospital is the major government healthcare institution located at the district headquarters. The Community Health Centres (CHCs) are set up at the headquarters of the health blocks. In the block level, there are Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) or Ayushman Arogya Mandirs (AAM) and Primary Health Centres (PHCs), as well as Health Sub-Centres (HSCs), which have not undergone the conversion to HWCs. The major challenge in the block-level health care system is the lack of medical professionals and healthcare workers. For instance, the conversion of HSCs and functioning of HWCs are not regularized due to the lack of Community Health Officers (CHOs) who were to be recruited by the state. Therefore, the beneficiaries are unable to avail medical assistance from institutions in their proximity, and are obliged to avail it from either private institutions or government institutions, which are not near their area of residence.

I also had a first-hand experience with the healthcare system of the district when I was diagnosed with a medical condition, while at the location. I was admitted to the Sadar Hospital, and I got to understand that the availability of doctors is not regular there after the Out-Patient timings are over. The Emergency Doctor was given the charge of attending to all the cases of the hospital. Also, the community members once shared that, since there is no caesarean delivery facility available in the hospital, even for birth complications, they do not prefer to be admitted here for delivery, and they choose private hospitals over the government institution in spite of the higher expenditure. Certain communities of Simdega are highly prone to Sickle Cell Anaemia, and a majority of the total population is susceptible to Anemia.

The Anganwadi Centres also act as the channel for disseminating healthy practices, resources, and Early Childhood Education. But the delivery of supplementary nutrition kits are not observed to be regular, which causes an ineffective factor in the system. The VHSNDs are conducted on a regular basis, led by the ANMs, assisted by Anganwadi Sevikas and Anganwadi Sahayikas. They are found to be highly active in doing their work and providing the best possible service to the beneficiaries despite the limitations they face.

The education system of the district is also well-established. The total number of government schools in the district is 758, and the total enrolled students in these government schools are 55,864. The total number of teachers employed in the government schools of the district is 2,424. Apart from these schools, there are KGBV Schools, JBAV Schools, as well as Ekalavya Residential Schools in the district. The higher education system is also having a good foundation in the district; Degree Colleges, Nursing Colleges, Teachers Training Institutes, Industrial Training Institutes, etc., are established in the district.

The major challenge faced with regard to the education system of the district is dropout. The number of students dropping out of school after secondary education is comparatively higher in the district, with the district average of this transition rate being 59.7%. The lack of motivation and guidance, as well as economic reasons, are the major issues faced by the students here. Irregularity of the students in attending classes also adds to this issue. In government residential schools, the shortage of teaching and non-teaching staff is the most important drawback; the staff are not ready to reside and work in the remote belts of the district for a nominal remuneration.

The accessibility to central and state schemes in health, education, livelihood, agriculture sectors, and so on; entitlements related to Forest Rights through a dedicated State Government scheme named Abua Bir Dishom Abhiyan, PM-JANMAN scheme for the PVTG communities, all these welfare initiatives by the government are made obtainable to the communities of the district. An important institution that brings together the grassroots-level community members is JSLPS. JSLPS aids in the formation of Women Self-Help Groups (SHGs), Village Organizations (VOs), and Cluster Level Federations (CLFs), which empower women of the district and thereby their families. Other than JSLPS, Cooperative Societies, and Farmers Producers Organizations (FPOs) bring together communities for their empowerment and well-being.

Apart from these government institutions and services, there are a number of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) operating in the district that sensitise and empower the local population. They complement government efforts by promoting participation, enhancing local capacities, and supporting the overall development of the people in the district.

Status Of Development

To address various developmental challenges prevailing in the district, quite a few incremental and transformational approaches have been undertaken through central and state government schemes and district-level approaches. Various methods have been undertaken by the district anchors as well to tackle the developmental challenges of the district. Simdega was previously affected by Left-Wing Extremism (LWE), but just three years ago, the district was officially declared free of LWE activities. This change was gradual and took considerable time. A key factor contributing to the decline of extremism has been the construction of roads. Improved road connectivity made remote and difficult-to-reach areas more accessible to the general public, enhanced security presence, and strengthened communication networks, making it increasingly difficult for extremists to maintain control over their territories. Simdega received Special Central Assistance (SCA) funds during the period when it was classified as a Left-Wing Extremism (LWE) affected district.

An approach undertaken by the school authorities of the district to resolve the issue of low attendance in the rural population has been appreciated and adopted all over the district. Diagnosis and treatment of the problem, and motivation are ensured by the campaign ‘Seeti Bajao Upasthithi Badhao’. This campaign engages students in motivating their fellow schoolmates to attend school by nudging them through a whistle. The whistle sound reminds the students and their families of the importance of attendance in the education system. The campaign initiated in Simdega district is now being replicated all over Jharkhand to tackle the issue of low attendance.

DAY- NRLM and JSLPS projects like Mahila Kisan Sashaktikaran Pariyojana (MKSP), Jharkhand Opportunities for Harnessing Rural Growth (JOHAR), Jharkhand Horticulture Intensification by Micro Drip Irrigation (JHIMDI), Aajeevika, Start-up Village Entrepreneurship Programme (SVEP) etc., is in the process of enhancing the livelihood of the communities. ‘Mahila Lakhpati Kisan Initiative’ helps in enhancing the livelihood of the households of the district by providing them knowledge and services to be involved in more than one income generation activity and to gain an annual income of more than 1 lakh Rupees.

The establishment of Nari Adhikar Kendras (NAK) and Gender Resource Centres (GRC) provides a platform to raise their issues and rely upon when in trouble, thereby helping themselves to be empowered. Their social development and entitlements are ensured through these institutions. Issues like domestic violence, ill-happening due to superstitions, issues caused by alcoholism by men in the family, etc., could be resolved through gender resource centres.

The Aspirational District Programme and Aspirational Block Programme are bringing about commendable differences in the district as well as the Aspirational Block, Bansjor. Provisions are delivered to the district to bring about the best outcomes and to grow as far as other developed districts of the nation. Simdega has been honored with monetary awards on multiple occasions by NITI Aayog for demonstrating outstanding performance across various sectors.

Intervention Design

The Problem

The people of Simdega encounter significant challenges in sustaining their livelihoods, leading to stagnation in income opportunities. Limited awareness of scientific practices keeps them dependent on traditional methods, while a lack of knowledge about available market options further restricts their growth. In this context, highlighting the untapped potential of lac cultivation offers a promising pathway to create sustainable livelihood opportunities through the adoption of scientific techniques and effective market linkages.

Jharkhand is one of the leading producers of lac in the country. In the Final Report on ‘A Value Chain on Lac and Lac-based Products for Domestic and Export Markets’, it is stated that “West Singhbhum, Gumla, Simdega, Latehar, Palamau, Garhwa, Ranchi, and Khunti districts of Jharkhand are the major lac-producing areas. In these areas, the principal host plants for the lac cultivation are palas (Butea monosperma), kusum (Schleichera oleosa), and ber (Ziziphus mauritiana)” (Prasad, N. 2014.). Simdega is one of the districts in the state that has the highest potential for lac production and processing. But despite the district having this potential in the production of lac, its cultivation is confined to the traditional methods, which produce low yields, and the newer scientific methods are unexplored; moreover, the processing of lac is also not effectively established in the district. I think that this is an important issue considering the livelihood augmentation in the district through NTFPs; if the available potential is un-utilized, the livelihood of the people which could have been enhanced remains an unattainable target.

The key stakeholders involved in this problem are the people involved in the cultivation and collection of lac, who are mainly people residing in the forests, the tribal population, PVTGs, other people residing in proximity to the forest area, and the farmers who are involved in the advanced cultivation of lac on host plants. Apart from the above-mentioned list of stakeholders, the District Administration, Simdega, and other line departments aligned in lac cultivation were the stakeholders involved in the resolution of this problem.

The research of secondary data I carried out in the initial days of the fellowship to understand the district helped me in discovering the tip of this problem. I came across a number of fact sheets and research papers that indicated the potential Simdega district has in the production of lac due to various environmental and geographical factors.

Additionally, the interaction with the community members during field visits made me realize that though the potential is high, it was not bringing in much to the people here. They are unaware of the fortune they possess and were exploited by others who then gain profit out of what these rural households could have earned.

Discussions with district and block-level officials, as well as community members, helped me understand the intensity of the problem. From the District Cooperative Office, the information regarding the lac processing units established in the district was received, but it was observed that none of the processing units were functional.

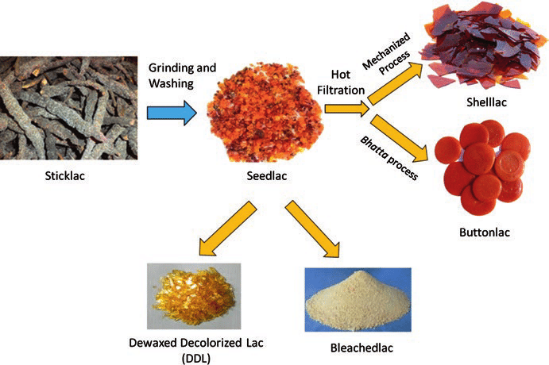

I had also visited a lac host tree plantation, wherein I got to interact with the farmer who shared that the government MSP for lac is lower and the market price is highly fluctuating, because of which people are not finding the cultivation of lac a primary livelihood opportunity. To address these challenges, a reverse strategy can be applied by processing raw lac into a form that is suitable for storage. The crude or stick lac, being unprocessed, cannot be stored effectively. However, once converted into seed lac, which is a storable form, it can also be further refined into higher-value lac products. Figure 1 illustrates the different stages of lac processing. The stick lac could be converted to seed lac which is the primary processed form of lac, suitable for storage. The seed lac could be processed to lac flakes which is the processed form of lac. Shellac could be produced from this, which is the purified form of lac processed in ethyl alcohol-based solvent, having the highest market value. The stages of production of lac is as given below:

Stick Lac -> Seed Lac -> Lac flakes -> Shellac

The paper on ‘Small Scale Lac Processing Unit for Seed lac’ by Niranjan Prasad et. al mentions that “mostly lac growers sell stick lac immediately after scraping due to associated storage problems. Proper storage of stick lac requires large space with adequate ventilation. Such facility may not available in lac growers’ houses. If stick lac is stored in bags, it forms lumps which are difficult to crush during processing. Further lump formation leads to deterioration in quality of lac. The stick lac converted into seed lac can be stored like grains in bags or bins” (Prasad, N. et al). If market linkage opportunities for basic processed lac (seed lac/lac flakes) are identified in advance and cultivators are directly connected with lac industries within the state or neighboring states, their reliance on middlemen in rural haats for sales can be eliminated. Moreover, with primary processing already undertaken, storage will no longer pose a problem, allowing farmers to sell their produce once market prices become favorable, aligning with how the project has been designed.

The problem on lac cultivation is a subset of a larger problem which involves the larger picture of untapped NTFP in the district. Simdega is known for its production of tamarind, sal leaves, mahua flower, mahua seeds, karanj, chiraunji, gum karaya, lac and so on. In the report of the project on Survey of Important Non-Timber Forest Produces and Estimation of Productivity and Production in Jharkhand, it was mentioned that “one-third people living in and around forests derive their livelihood support from the collection and marketing of NTFPs. But, due to lack of proper procurement of these products, its marketing is hence forth affected. The people residing near forests collect the NTFPs during its peak season and sell it for their livelihood in local haat at the earliest due to absence of storage facility. Traders procure these NTFPs from them at some perceptive rates through middle man (bicholia) and sell at those places, where the demand was more. Many a time, the quality of collected materials deteriorates due to premature or post mature collection/harvesting, weather etc. Therefore, they tried to keep maximum collection to get nominal revenue. Various Self-Help Groups (SHGs), PACS, LAMPSand Cooperative Societies were also available at grassroot level for procuring and marketing of NTFPs. But their presence was limited so they prefer the bicholia. The lac cultivators nad collectors sold maximum materials either directs to local buyers or some time to JHAMFCOFED through cooperative societies like: Primary Agriculture Credit Society (PACS), Vyapar Mandal Shayog Samiti (VMSS), Primary Minor Forest Produce Cooperative Societies (PMFPCS), Women SHG or Reputed NGOs” (Pandey, K. 2018)

The Intervention Design

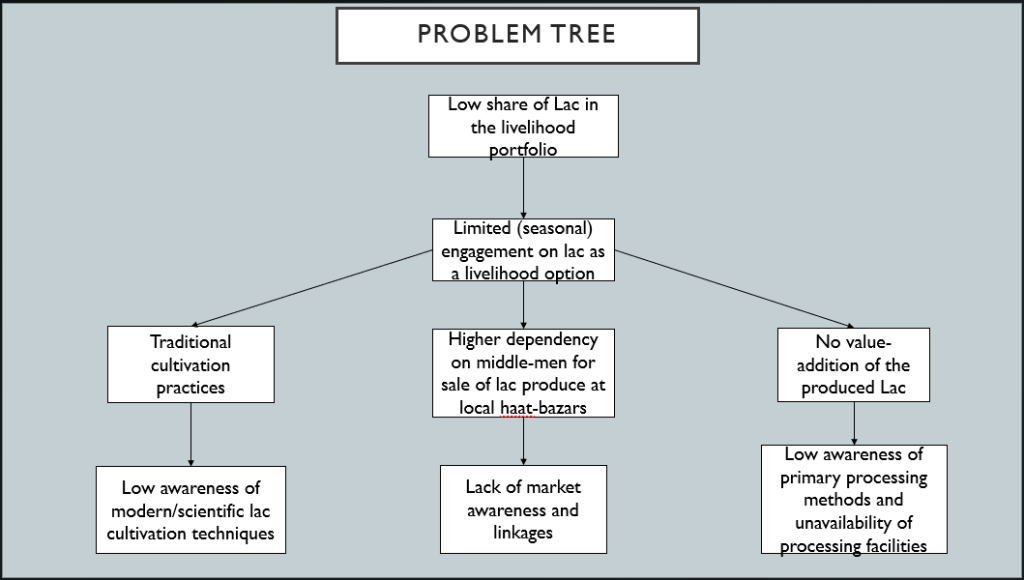

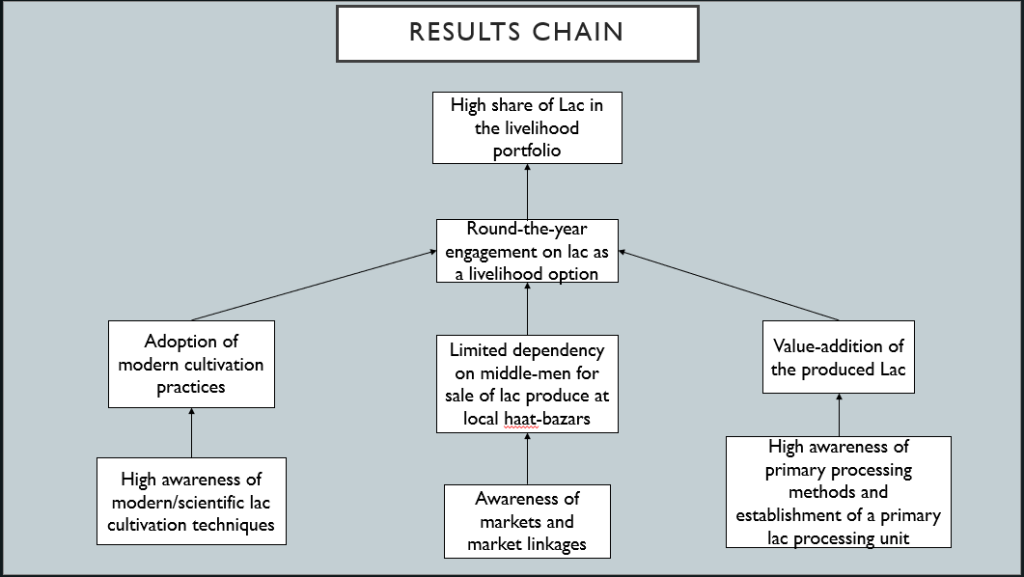

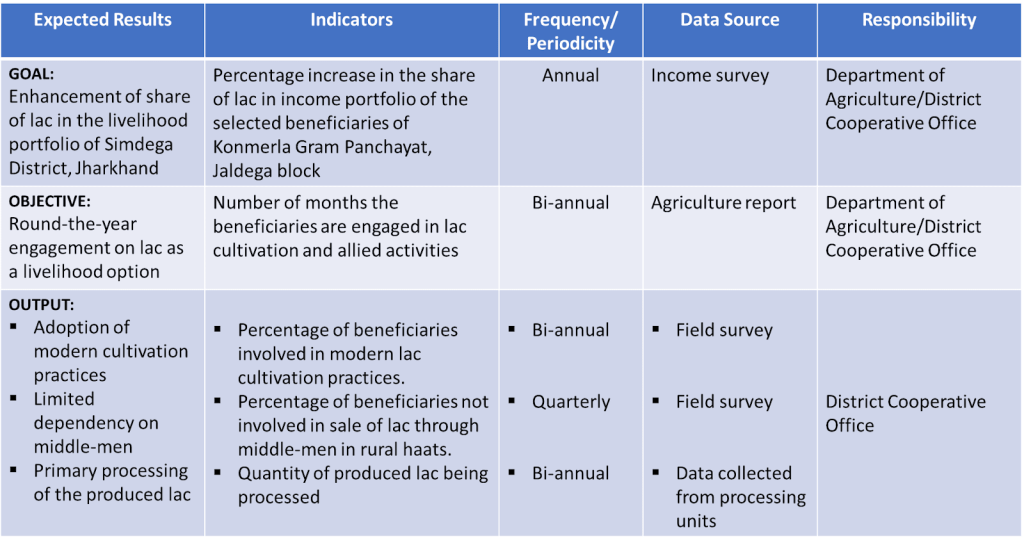

The intervention is based on the enhancement of lac-based livelihood opportunities in Simdega district, Jharkhand. The objective is to approach the lac portfolio of the district holistically, with the objective to increase the share of lac for livelihood enhancement of the cultivators and thus equipping the district to be a leading producer of one of the forest products in great demand in pharmaceuticals, in the manufacture of cosmetics, ornaments, electrical insulation materials, polishes, sealing wax and so on. The intervention aims to increase the share of lac in the livelihood portfolio by ensuring round-the-year engagement of farmers in lac cultivation as a sustainable livelihood option. This is supported through three pathways which are the adoption of modern cultivation practices, driven by enhanced awareness of modern and scientific lac cultivation techniques; reduction in dependency on middlemen for the sale of lac produce at local haat-bazars, enabled by improved awareness of markets and market linkages; and value addition of produced lac, achieved through increased awareness of primary processing methods and the establishment of a primary lac processing unit.

Lack of knowledge on the scientific and modern techniques being a major issue, training on the scientific lac cultivation techniques could be provided to the lac cultivators. An informed set of cultivators could help attain adequate production of lac that could equip the district to be its leading producer and could also be self-reliant in terms of raw lac for primary processing. On being aware of higher profit-generating market linkage opportunities, the cultivators would refrain from being dependent on middlemen for the sale of the raw lac. Also, the challenge in storage could be tackled upon the establishment of a primary lac processing unit, which could be utilized for processing the crude lac to lac flakes, which could be stored without any quality issues.

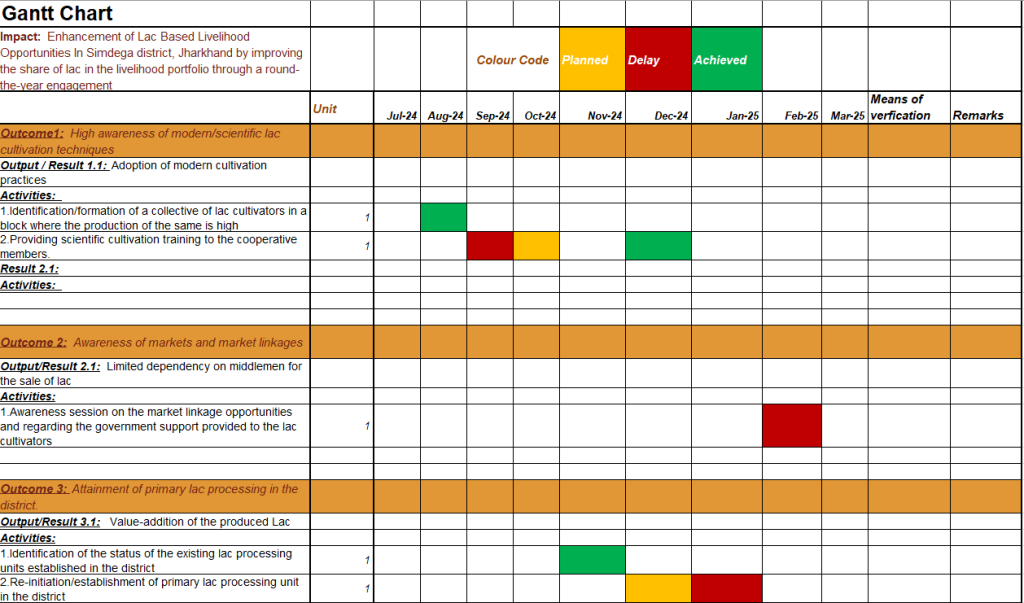

A blueprint of the intervention is prepared, which includes the pitch deck, project proposal, and Gantt Chart, mentioning the tentative budget and timeline of the project. For initiating the project, an initial conversation was conducted with the concerned stakeholders. The Deputy Commissioner, District Program Manager – JSLPS, District Cooperative Officer, and District Entrepreneur Coordinator were informed regarding the project to create a collaborative platform for the implementation of the project.

With the support of the officials, three panchayats were shortlisted for the implementation of the project. This was done by considering various factors, including the level of production of lac, the presence of Lac Cooperatives, Lac Processing Units, etc. The panchayats shortlisted were Konmerla and Lomboi in Jaldega block and Kumbakera in Bansjor block. All three panchayats have the potential for high production of lac and the presence of Multi-Purpose Cooperative Societies (MPCS), wherein the lac cultivators are also members. Konmerla Panchayat was the panchayat that already had an established Lac Processing Unit.

Field visits were conducted to obtain a deeper understanding of the information required for the implementation of the project. An observation visit was conducted at a Semialata plantation site. The cultivator shared that semialata plants are the most suitable host for the lac insects and help in the production of the best quality lac in comparison to other traditional host plants, including palash, ber, or kusum trees. The semialata plants are shorter as well, which makes it convenient in the harvesting process. Therefore, the focus will be to inculcate modern lac cultivation practices in the farmers, which includes the lac cultivation on semialata as the host trees. “Integration of vegetable crops with F. semialata showed a significant increase in shoot length for lac insect settlement, lac encrustation length, and sticklac yield over sole lac culture at both the planting patterns and vegetable crops schedules” (B.P. Singh et. al. 2014)

Field visits were also organized to certain Lac Processing units, where I got to observe the machinery used in the processing of lac. The units have to be made completely functional through a sustainable supply of raw lac; this is the major objective of the project.

Challenges

The most important and serious challenge faced during the formulation of the proposal for the project was the budget constraints in the district. Since Simdega district is not eligible for funds through Special Central Assistance (SCA) for the districts affected with Left-Wing Extremism, nor are the funds through District Mineral Fund Trust (DMFT) a substantial amount.

Aside from this, a serious issue identified was in mobilizing the cultivators and cooperative members. There are around 20 cooperatives formed in the district for engaging people in the production of lac for a livelihood, and these cooperatives are linked to a processing unit, subject to the presence of the unit in the geography of the cooperative. These cooperatives have members of SHGs as well as other lac producers. But these cooperatives are not functioning actively, as the lac procurement through internal production (production of lac by the members of the cooperative) is not sufficient for the processing and for the external procurement (procurement of raw lac from the market), there is a limitation of capital availability.

Also, the dependence of cultivators on traditional methods of lac cultivation is becoming a significant hindrance since it does not yield enough raw lac for processing. Because of this, none of the units were completely functional as the production within the district by the farmers is not sufficient for keeping the unit functional over the year, and the financial limitations restrict the cooperatives from procuring lac for processing through external sources.

Also, all the units established in the district are small units; the machinery in these units is of lower capacity, which makes the processing financially less viable, while the effort required remains high. Therefore, a majority of the existing units have to be re-initiated by establishing machinery of higher capacity.

“The major risk factors identified are mortality of lac crop during fog, especially on Ziziphus mauritiana (Ber) and Schleichera oleosa (Kusum); non-remunerative market price of lac; spider net on host tree resulting in trapping of crawlers; and lack of technical knowledge on lac cultivation” (A.K. Jaiswal et. al. 2003).

Apart from these risk factors, the under-utilization of the resources is another issue. “Major lac host plants including Butea monosperma, Schleichera oleosa, and Ziziphus mauritiana are distributed across natural forests, roadside, near agricultural land, and around villages in the Chotanagpur plateau comprising Jharkhand and its adjoining states. But most of those resources are lying underutilized due to lack of awareness and only 5% of host plants of S. oleosa and Z. mauritiana are being utilized for producing Kusmi strain of lac” (D.H Patel et. al. 2022)

The project is designed in a manner that the risk factors are considered and analysed to overcome these major elements of threat. In order to tackle the mortality of lac crops during fog on ber and kusum trees, the usage of semialata plants will be promoted as host plants, which do not have this issue. In order to keep lac cultivation as a sustainable source of income, it could be taken up as a secondary livelihood opportunity initially and then converted to the primary activity after a period. The non-remunerative market price of lac could be resolved by exploring the industries where market linkage could be done by ensuring a reasonable pay to the farmers. The processing of lac to a storable form could help deal with the fluctuation of the price of lac in the market, so that lac stored after processing could be sold once the price is reasonable in the market. The challenge regarding the lack of technical knowledge will be resolved by an intensive training of the lac cultivators on the modern and scientific lac cultivation practices by experienced resource persons from premier institutions like the Indian Institute of Natural Resins and Gums (IINRG), Ranchi.

Intervention Implementation

An observation visit was conducted to the shortlisted panchayats, which helped in laying the foundation for a focused field engagement. Building on the observations from the initial visit, a comprehensive field visit was subsequently organized to each of the panchayats. The primary objective of the visit is to interact directly with members of the MPCSs who are involved in lac cultivation. These interactions proved to be highly beneficial, which offered me a deeper understanding of the ground realities faced by the cooperative members.

Through in-person conversations, I received insight into the aspirations, future plans, and possible foreseeable challenges according to the members with regard to lac production and processing. They shared their aspirations for scaling lac production and enhancing processing techniques to augment their lac-based livelihood opportunities. The members of two out of three cooperative societies revealed a strong sense of ownership and ambition, particularly in exploring value addition, accessing better markets, and adopting sustainable harvesting practices. At the same time, they also spoke about challenges such as climate-related vulnerabilities, market fluctuations, and so on. These discussions provided critical input for planning more responsive interventions. By engaging with the community directly, the field visit highlighted the importance of participatory development and the need to co-create solutions with the stakeholders themselves.

The previously shortlisted panchayats for the project included Konmerla and Lomboi in Jaldega block, and Kumbakera in Bansjor block. After a thorough assessment of various parameters, the focus area was finalized as Konmerla Panchayat in Jaldega block, Simdega district. This decision was based on observations made during field visits and direct interactions with members of the cooperative societies in the shortlisted regions. Konmerla came out as the most feasible location for implementing the project due to several key factors. Most importantly, the panchayat has an active MPCS with approximately 200 members, and around 50 members are involved in lac cultivation; this reflects strong community involvement in comparison to that in the other shortlisted panchayats. Additionally, the cooperative members were provided with essential toolkits required for lac cultivation and harvesting. Also, Konmerla has a small-scale lac processing unit, which adds value to the local production and provides opportunities for income generation and added infrastructure support. Another significant advantage is the availability of numerous plantation sites within the vicinity of the panchayat with lac host trees. These include both individually owned and publicly managed plantations, offering a high scope for expanding lac cultivation. These favorable conditions add to considering Konmerla as an ideal site for implementing the project, which could hopefully offer a strong foundation for sustainable lac development and community engagement.

A field visit was also conducted to a plantation site in Jaldega block (figure given below) developed as an initiative by the Department of Agriculture, Animal Husbandry, and Cooperatives. I accompanied the District Cooperatives Officer (DCO) to visit this site. The plantation site, located in Konmerla Panchayat, spans approximately 2.50 acres and features multi-cropping of various lac host plants, including kusum, ber, and semialata, along with other plants. “Integration of vegetable crops with F. semialata showed a significant increase in shoot length for lac insect settlement, lac encrustation length, and sticklac yield over sole lac culture at both the planting patterns and vegetable crops schedules.” The initiative promotes lac cultivation by establishing a dedicated and well-maintained plantation that can serve as a model for replication in surrounding areas. The multi-cropping system not only enhances biodiversity but also ensures the availability of multiple host options for lac insect inoculation, thereby increasing the resilience and sustainability of lac production. Once the plants reach maturity, they will be inoculated with lac insects, marking the beginning of the lac production cycle. This intervention is expected to boost local lac cultivation and provide lac-based livelihood opportunities to the communities. The plantation site holds significant potential for training, demonstration, and awareness-building activities, making it a beneficial intervention for both the project and the local community.

In addition to these, a visit was also undertaken to a large-scale lac processing unit (Figure given below) located in Kolebira block of the district. The unit, currently owned by a private individual, is expected to be procured by JASCOLAMPF in the near future. Once the acquisition is complete, the facility could be utilized for processing lac produced across various blocks of Simdega. This could be highly significant for the processing of lac in the district, as there are currently no other large-scale lac processing units established within Simdega district. The operationalization of this facility under JASCOLAMPF’s management could greatly enhance local processing capacity, reduce the need for transportation of crude lac, which cannot be stored for a considerable time period, to distant units, and provide better value addition opportunities for local producers. “The sticklac converted into seedlac can be stored like grains in bags or bins. The process of making seedlac from sticklac involves five major unit operations i.e. crushing, washing, drying, winnowing and grading” (Prasad, N et. al). The unit has the facility for all these four operations. Moreover, it could serve as a centralized hub benefiting lac cultivators and cooperative members across Simdega. The unit’s potential to transform the lac value chain makes it a critical asset for the district’s lac-based economy.

The project encountered a few deviations from the original plan, which required few adjustments in the implementation. Due to certain circumstances, it became important to revise the initial strategy and make improvisations on the go to ensure smooth execution. I have taken care to keep the objectives of my project intact, but the path for achieving them had to be adapted based on the challenges faced on the ground. One of the major challenges faced during the project was mobilizing funds. Although I had anticipated this as a potential bottleneck early on, I was hopeful that feasible solutions would appear along the way. However, despite my expectations, the situation did not unfold as envisioned. Mobilizing financial resources became more difficult than initially assumed, affecting the pace and scope of certain project activities. During instances like these, where the planned resources, solutions, or approaches were not available or viable, it was important to explore and identify alternative possibilities. It is required to maintain a flexible and responsive approach, allowing for modifications that align with the changing context. Although these changes were unplanned, they were necessary to overcome obstacles and continue progress toward the desired outcomes. Such adjustments reflect the dynamic nature of field-based projects and the importance of resilience and adaptability in implementation.

Challenges

As I have mentioned earlier, the project implementation plan has undergone certain deviations, and these deviations have arisen due to the occurrence of certain challenges. One of the most significant challenges encountered during the project was the budget constraint resulting from limited fund availability in Simdega district. This financial limitation became a major hurdle in the implementation of several planned activities. As a result, I was unable to carry out some of the core activities of the project as planned.

A key activity that had to be put on hold was the training program on scientific lac cultivation practices for the members of the cooperative. These sessions were designed to equip members with technical knowledge and practical skills to enhance lac production. This was a significant component of the project plan. However, due to the lack of necessary funds, it was not feasible to organize the training. Similarly, an exposure visit to Khuti Lac Processing unit, which was planned to give cooperative members first-hand experience and learning from successful lac cultivation models in other areas, also had to be withheld for the same reason. These setbacks have affected the capacity-building efforts of the project and limited the opportunities for knowledge enhancement among stakeholders.

The second major challenge faced during the project was maintaining the motivation levels of cooperative members over time. Initially, through regular engagement and consistent interaction with members of the pre-existing but largely inactive cooperatives, significant progress was made in regaining the momentum of the group. Many members began to participate more actively in lac cultivation and expressed genuine interest in improving their livelihoods through lac-based activities. Their renewed enthusiasm played a key role in strengthening the cooperative. However, sustaining this motivation proved to be difficult, especially in the absence of critical support activities. Due to budget constraints, I was unable to organize training sessions on scientific lac cultivation practices or arrange exposure visits—both of which were essential components of the project. These activities were intended to build technical capacity and broaden the understanding of the cooperative society members through a first-hand learning experience. Without these opportunities for skill development and external exposure, it became obvious that some members began to lose interest and momentum. Besides these, the access to meagre, yet immediate income through the sale of crude lac in the rural haats is always open for them. “In case of lac crop, farmers try to sell the brood lac as such. In case it was not sold on time, they scrap the lac from its stick and sell it in the local market” (Prasad, N. 2014). This also adds to their decreasing motivation since they are aware of a source of income they could always rely upon, though that income is insufficient for sustaining their livelihood. It is evident from this that in community-based projects, continuous capacity-building and motivational support are of prime importance.

Outcomes and Impact

My intervention to enhance lac-based livelihood opportunities in Simdega district, Jharkhand, has strengthened the scientific understanding of cooperative members regarding lac cultivation practices. Through capacity building and awareness efforts, the members have gained improved technical knowledge, enabling them to adopt better methods for lac production and management. While cultivation practices are being streamlined, the full potential of primary lac processing in the district will be realized once the large-scale lac processing unit is revived. The revival process is currently underway and, once operational, it will significantly contribute to improved storage, value addition, and sustainable market opportunities for lac cultivators.

In order to adapt to emerging insights and on-ground realities, the project has experienced several key shifts throughout its implementation trajectory. One significant pivot was the discovery and inclusion of existing, underutilized resources within the district. Initially, the project blueprint did not account for these assets, as the focus was primarily on creating new infrastructure and systems to support lac cultivation and processing. However, during a detailed exploration of lac-related resources across the district, it became evident that a large-scale processing unit, though currently non-functional, could be revived and integrated into the project framework.

Recognizing the potential of utilizing this defunct facility brought about a strategic change in direction, optimizing existing resources rather than investing solely in new ones. The initial plan was to establish a processing unit, but since a significant resource was explored, the plan is to revive the unit and keep it functional for sustaining the lac processing in the district. The net profit that could be incurred from the processing of lac in this unit was also calculated, and it was found that per kilogram of lac processed, a profit of Rs. 70 could be earned. Upon sustaining the processing of lac in this unit, a substantial amount could be gained as profit, which could be shared amongst the lac producers. This is a very significant change that could be brought about to the lives of the lac cultivators in the district.

The deviation from original plan had also altered the implementation timelines. Consequently, the project evolved from its original plan to a more practical and resource-efficient model that capitalizes on what is already available within the district, ensuring sustainable growth and impact. Also, the plan to conduct a training on scientific lac cultivation to the cooperative society members of the shortlisted panchayats was a part of the initial plan. But, due to the lack of necessary funds, it was not feasible to organize the training. Later on, the lac cultivators were linked to training that was conducted by the SIDHKOFED in collaboration with IINRG. In this quarter, a training program was organized in Khunti, in which 36 members of Konmerla MPCS had also taken part. This was a comprehensive training in which scientific lac cultivation techniques were discussed.

Effect and Impact Of The Intervention:

The project, though it has not unfolded as envisioned by me while preparing the blueprint, has created certain small changes in the lac profile of the district and diversified the livelihood options for members of the cooperative society, contributing positively to their income sources.

On interacting with the cooperative members of Konmerla panchayat, I came to understand that they are interested in creating a livelihood out of lac as one of the multiple livelihood opportunities. This is because the lac market is highly volatile, so they prefer to treat it as a supplementary source that complements their main income activities. “Lac being mostly a subsidiary occupation however providing much-needed cash income in low agriculture activity seasons in Jharkhand” (Magry et al., 2017). The enthusiasm of these lac producers was guided in the right direction. The lac harvested this season will be processed locally within the district itself, which is a positive development. Additionally, the members have received training in scientific lac farming methods, enhancing their skills and knowledge. These efforts are collectively helping to build a proactive community invested in strengthening the district’s lac sector. Their progress and dedication could serve as motivation for lac cultivators in other panchayats and blocks, encouraging them to adopt similar practices and contribute to the district’s expanding lac portfolio.

The exploration of lac-related resources in the district resulted in discovering a large-scale lac processing facility. This unit, which had been non-functional, is now being revived and brought back into operation. Restoring and upgrading this facility has the potential to significantly transform the district’s lac economy by boosting local lac processing capacity, adding value to raw lac, and improving the storability of the lac for enabling the cultivators to hold stocks till the sale when market exhibits a positive trend. All these ultimately strengthens the overall economic framework surrounding lac production in the region.

Thus, it could be said that the project has partially accomplished the intended outcomes of the project, but not in a manner envisioned initially. The unintended positive outcomes have also occurred in the implementation trajectory, such as the identification of the large-scale lac processing unit, which was not anticipated in the initial design. The contextual factors, such as the level of enthusiasm of the cooperative members, have positively affected the project. However, certain administrative aspects, mainly the economic constraints, have hindered the implementation of some activities of the project.

Inhibiting Factors

As previously stated, the project’s implementation has seen some deviations from the original plan, mainly because unexpected challenges emerged during its execution. These challenges made it necessary to modify the initial approach, leading to changes in certain planned activities to better address the realities on the ground. As a result, the implementation strategy has to be redesigned in some areas to ensure that its objectives can still be met effectively despite these practical constraints and evolving conditions.

The major hurdle faced, and which continues to persist, is the shortage of funds, limiting the execution of several planned activities. However, I tried to explore alternative solutions, which led to the discovery of a privately owned lac processing unit that is now in the process of being revived. To support the beneficiaries, they have been connected to government-run training programs to enhance their skills. Additionally, efforts have been made to ensure that the distributed seed kits and tool kits are used effectively and contribute meaningfully to improving lac cultivation practices, thereby maximizing the benefits despite financial constraints.

Sustainability Plan

The cooperative members were linked to the lac seed distribution program which will be conducted annually, during which JASCOLAMPF will provide lac seeds to cooperative members to support the upcoming cultivation cycle. This initiative aims to assist lac cultivators by supplying quality seeds to boost production. Members from the Kolebira, Bano, and Jaldega blocks will benefit from this round of seed kit distribution, helping them prepare for the subsequent cycles and strengthen their livelihoods through improved lac cultivation practices. They have also been provided with toolkits essential for lac cultivation, which serve as an asset that can be repeatedly used across multiple cultivation cycles. As the MPCS members have been trained in scientific cultivation techniques, they can effectively utilize the provided seed kits and tool kits to apply these methods in the upcoming cultivation cycle. This will help them adopt better practices and potentially increase their lac yield and income.

To ensure that lac cultivation remains a favoured livelihood choice, it has been incorporated into the Discussion Points developed by the PPIA Fellows, Simdega. (The Discussion Points are a list of topics proposed to be addressed during various village and panchayat level gatherings, such as GPCC, Gram Sabha, VO meetings, CLF meetings, and similar forums). This aims to establish lac cultivation as a recurring agenda in various village and panchayat-level meetings and forums. The topic concerning lac has been placed under the broader theme of utilizing forest produce to strengthen and diversify income sources. By promoting lac as a supplementary livelihood option, the initiative seeks to encourage communities to adopt sustainable practices and benefit from forest resources, thereby enhancing their overall economic resilience and self-reliance, which in turn enhances the lac-based livelihood portfolio of the district.

On critically analysing the sustainability factor, certain steps have been made to include lac as a habit of the people whose lives are linked to lac in any manner. The utilization of the provided resources, including seed kits and tool kits, and the application of scientific methods could ensure the sustainability factor. The facility for lac processing that is under the process of revival in the district could also add to the sustainability plan. But sustaining the motivation of the lac cultivators is a major challenge that could affect the sustainability of round-the-year lac-based engagement. This is because of the instability of the lac market and the supremacy of the middlemen in the business. The rural lac producers could be easily distracted by the bait of instant income. “…Simdega district also witnessed tremendous growth in Kusumi lac. However, on account of lack of proper marketing the individual villager ends up getting meagre amount to the tune of Rs 550 per kg” (Kerketta. S., 2023). Yet the processing unit is expected to sustain the motivation of the lac cultivators.

Thus, summarizing my change story, though the project did not disclose exactly as initially envisioned by me, several strategic adjustments were made based on on-ground insights. One of the key developments has been the identification and revival efforts of a small-scale lac processing unit. This step is crucial to achieving the project’s goals and establishing a sustainable lac production and processing chain in the district. One of the major lessons I gained from this project is that ground realities often differ from the original implementation plan. However, such deviations should not diminish motivation or hinder progress. As an alternative, they should be viewed as opportunities to adapt and enhance the plan, exploring alternative pathways that still serve the core objectives and deliver meaningful benefits to the target beneficiaries.

Reflections and Learnings

Through the intervention I have undertaken on the enhancement of lac-based livelihoods in Simdega, I have gained a rich set of experiences and learnings. This intervention helped me understand the process of designing a project and how the on-ground realities unfold during implementation. Liaising simultaneously with government officials and community members was an entirely new experience for me. Typically, being placed with the District Administration, my work primarily revolves around designing projects and proposals in consultation with government entities and experts, relying largely on secondary research. However, this intervention offered me the opportunity to engage directly with both the administration and the community, bridging policy design with grassroots realities.

The set of learnings that I have gained can be articulated into public institution learning, community institutions learning, impact learning, and policy learning. I will be discussing my learnings under these typologies.

Public Institution Learning

My intervention on enhancing lac-based livelihoods in Simdega provided me with significant insights into the functioning of government systems related to Non-Timber Forest Produce (NTFPs). Through this experience, I gained an understanding of the various institutions that support lac cultivation and marketing in the district. Other than JSPLS, VDVK, and the Forest Department, I learned about the pivotal role played by the Cooperatives Division in promoting lac. The District Cooperatives Office, for instance, facilitates the formation of MPCSs and provides members with essential materials and resources required for effective cultivation.

I also became acquainted with JASCOLAMPF (Jharkhand State Co-operative Lac Marketing & Procurement Federation Ltd.), the organization under the Cooperatives Department dedicated to the promotion and development of the lac sector in Jharkhand. JASCOLAMPF supports lac growers primarily through the marketing and procurement of their produce, ensuring better returns for farmers. I also had the opportunity to learn about SIDHKOFED and incorporate it into my intervention. SIDHKOFED (Sidho-Kanho Agriculture and Forest Produce State Co-operative Federation Limited) is a state-level cooperative federation in Jharkhand that functions under the Cooperatives Department of the Jharkhand Government and plays a key role in promoting agricultural and allied activities through cooperative structures. In addition, I learned about other cooperative structures such as LAMPS (Large Area Adivasi Multipurpose Cooperative Societies), which cater to tribal and rural communities by offering services ranging from agricultural inputs and credit to marketing support. Similarly, PACS (Primary Agricultural Credit Societies) function as farmer-oriented cooperatives providing crucial services like storage, procurement, and marketing of agricultural produce. Understanding the roles and operational mechanisms of these cooperatives and government institutions helped me navigate the lac value chain more effectively. This knowledge has been instrumental in integrating cooperative structures into other projects, ensuring sustainable engagement with both the community and institutional frameworks. By observing how these systems operate, I was able to align my intervention strategies with existing support mechanisms, thereby enhancing the impact and scalability of lac-based livelihoods in the district.

Community Institutions Learning

The learnings from the community and their institutions have been invaluable, both for the design and implementation of my intervention and for my broader engagement in Simdega district. Interacting with the community provided deep insights into their daily lives, challenges, and aspirations. While understanding the problems they face was important, listening to their hopes and ambitions was particularly inspiring.

During my intervention, Multi-Purpose Cooperative Societies emerged as the primary stakeholder group. I focused on the MPCS of Konmerla Panchayat, Jaldega, which comprises of around 50 members with varying levels of interest and experience in lac cultivation. To strengthen their capacity, members were provided with scientific training programs, equipping them with improved knowledge and techniques for lac cultivation. Additionally, as part of the intervention, they were linked to the provision of essential assets, including seed kits and tool kits, to facilitate better productivity and sustainability.

Engaging directly with both the community and cooperative structures allowed me to align intervention strategies with local realities, ensuring that the initiative not only enhanced lac-based livelihoods but also supported the aspirations and resilience of the farmers involved.

Impact Learning

Although the project did not fully unfold as originally envisioned during the planning stage, it has led to several meaningful outcomes in enhancing the lac sector in Simdega. The intervention contributed to small but notable improvements in the lac profile of the district and helped diversify the livelihood options of cooperative members, positively impacting their income sources.

One of the most significant developments during the intervention was the identification of a large-scale lac processing facility in the district. This unit, which had been non-operational, is now in the process of being revived and upgraded. Once fully functional, this facility has the potential to transform the local lac economy by increasing processing capacity, adding value to raw lac, and improving storability. This would enable cultivators to retain their produce until favorable market conditions emerge, thereby enhancing their economic returns.

While the project partially achieved its intended objectives, the outcomes were realized in ways that differed from the initial blueprint. Some unexpected positive results also emerged, such as the discovery and initiation of the revival of the processing unit, which was not anticipated during project design. Contextual factors, including the motivation and enthusiasm of cooperative members, positively influenced project progress. However, certain administrative and economic constraints posed challenges that limited the full implementation of some planned activities. The significant learning that the intervention demonstrates is that even when a project does not unfold exactly as planned, it can still generate valuable impacts, uncover new opportunities, and contribute to long-term improvements in livelihoods and local economic systems.

Policy Learning

During my intervention, I gained substantial exposure to policies and programs relevant to my work, particularly those associated with cooperative federations and the range of services they provide to cooperative members. Understanding how these federations operate and support members—through capacity building, access to inputs, and market linkages—helped me align my intervention effectively within the existing institutional framework.

One key initiative that influenced the design of my intervention was the Mahila Lakhpati Didi program. This initiative aims to empower women by ensuring that each participant earns an annual income of at least ₹1 lakh through engagement in diverse livelihood opportunities. Recognizing the potential of lac cultivation as a complementary source of income, I structured my intervention to link it with such women-focused programs. By promoting scientific techniques of lac cultivation, the activity could provide a stable seasonal income to SHG members, supplementing their existing livelihoods and contributing to the overall goal of financial empowerment.

These are the learning that I have gained by planning, designing, and implementing this intervention in Simdega district.

References

- Central Ground Water Board. (2013). Ground water information booklet: Simdega district, Jharkhand. Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India.

- Prasad, N. 2014. Final Report of NAIP sub-project on “A Value Chain on Lac and Lac based Products for Domestic and Export Markets”. Indian Institute of Natural Resins and Gums, Namkum, Ranchi.

- Prasad, N et. al. “Small Scale Lac Processing Unit for Seed lac”. Indian Institute of Natural Resins and Gums, Namkum, Ranchi.

- Pandey, K. Report of the project on “Survey of Important Non-Timber Forest Produces and Estimation of Productivity and Production in Jharkhand” (2015-16 to 2017-18). Department of Forest, Environment & Climate Change, Ranchi, Jharkhand.

- Kumar, S. 2016 “Enhancement of Livelihood Activities Through Non-Timber Forest Products: A Study in Jharkhand’s Ranchi and Simdega Districts”. Jharkhand Journal of Development and Management Studies XISS, Ranchi.

- Mukhyamantri Laghu Evam Kutir Udyam Vikas Board – Departments – District Simdega NIC Portal.

- B.P. Singh and R.K. Singh. 2014: “Effect of Intercrops on Plant Growth, Lac Encrustation And Lac Yield In Flemingia Semialata Roxb”. Agricultural Research Communication Centre – Indian Institute of Natural Resins and Gums, Namkum, Ranchi.

- Shanta Rani Kerketta (2023): “Lac – A Good Source of Livelihood in Jharkhand”. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research (IJFMR).

- A.K. Jaiswal et. al. 2003: “Problems of lac growers in Jharkhand State”. Journal of Non Timber Forest Products

- D.H Patel and M. Ashwini. 2022: “Lac Cultivation: Issues and Challenges”. Agriculture & Food: E-Newsletter, Article ID – 38268